By Kitahara Megumi

Translated by Ikuko Sorensen

Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

Itō Tāri (Miwako Itō, 1951–2021) was a trailblazing Japanese performance artist and feminist activist who was always trying to break new ground and change the times.1 She passed away on September 22, 2021 from ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis). Now, the work of documenting and remembering Itō Tāri continues, led by her friends.

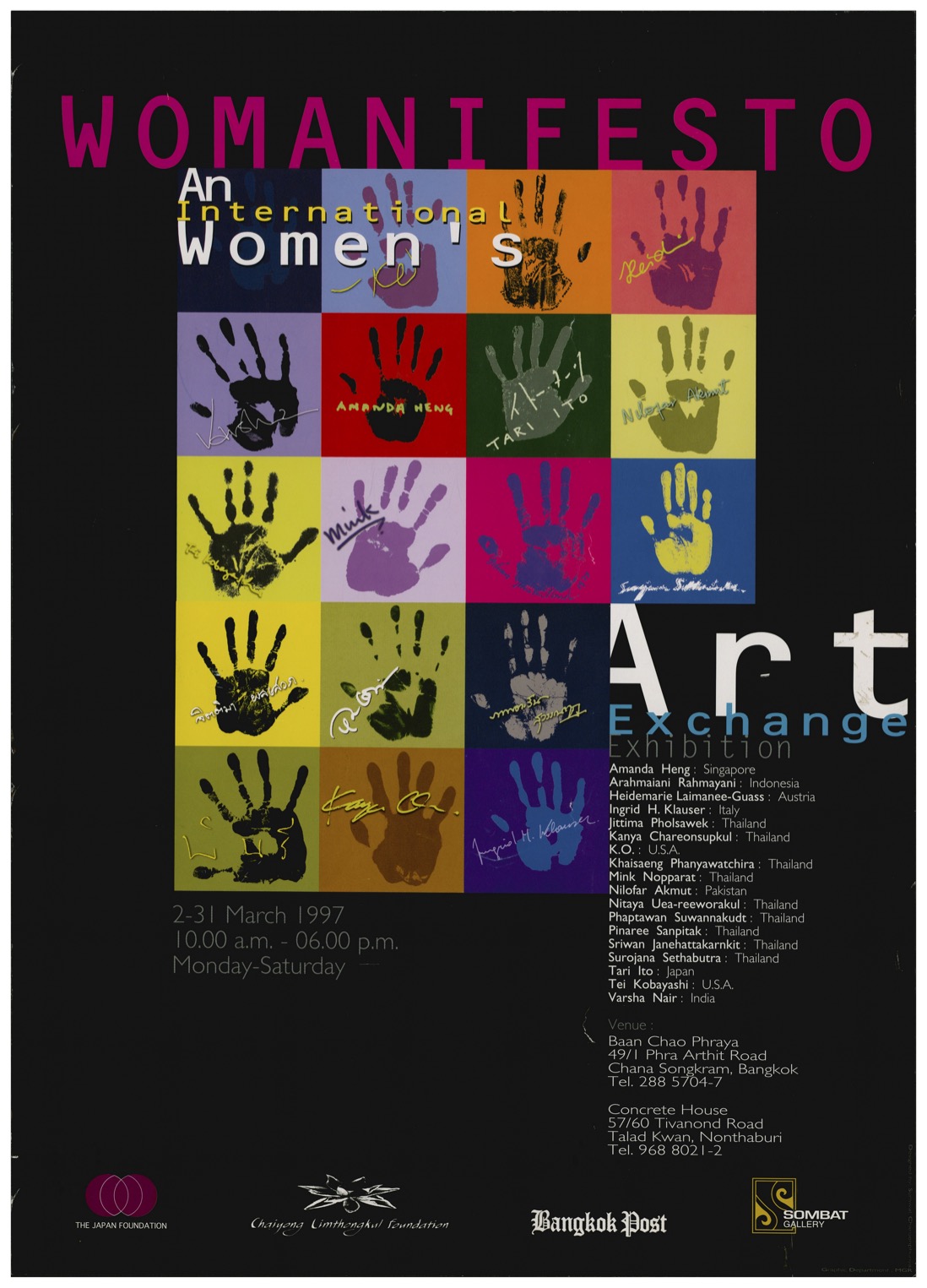

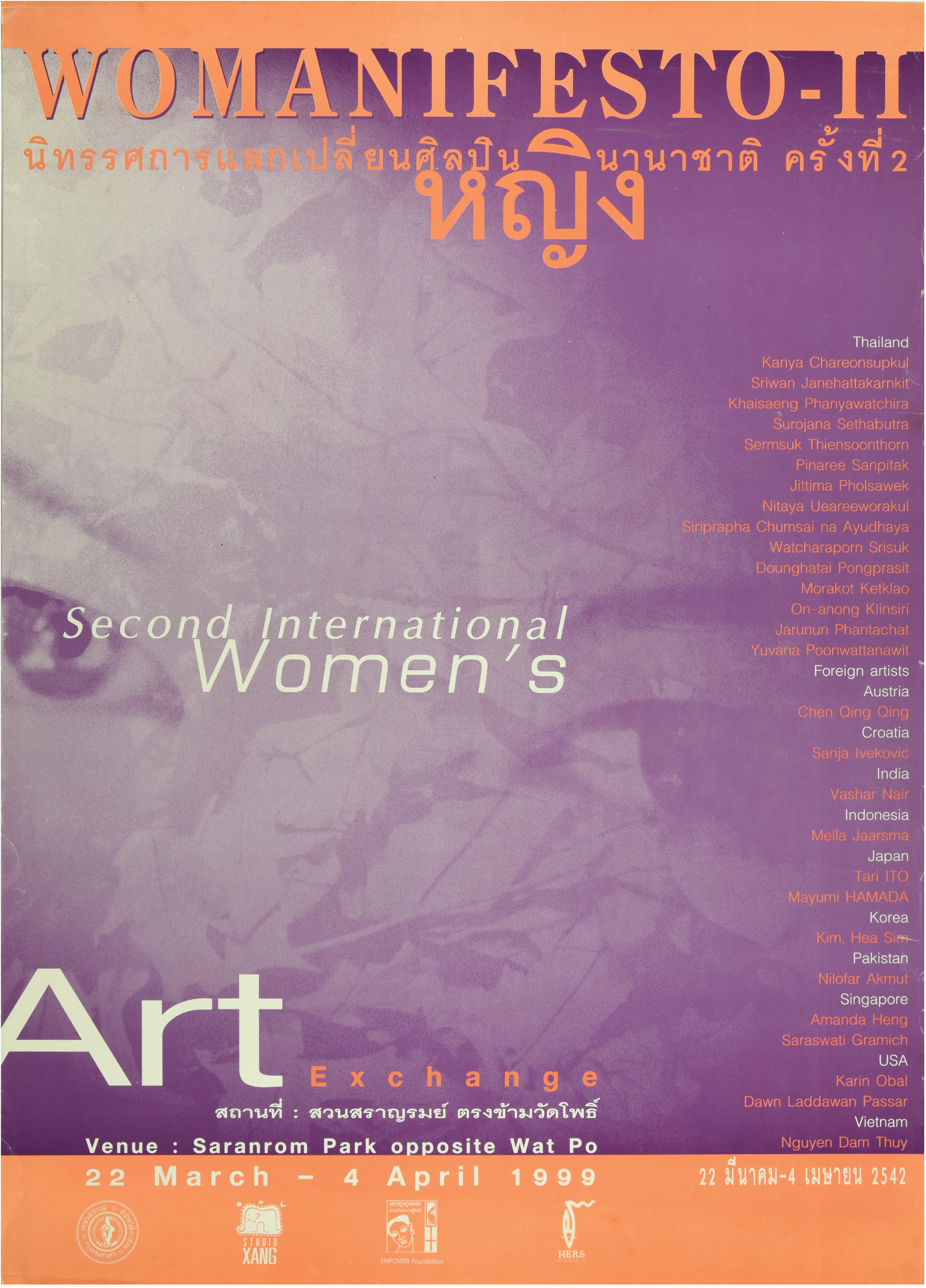

The relationship between Itō Tāri and Womanifesto is significant. She had participated and performed in ‘Womanifesto’, at that time an international women’s art exchange exhibition in 1997 and 1999. Although she participated twice only, the experience she gained there directly led to her subsequent networking of women artists in Japan and greatly influenced their activities. At the first ‘Womanifesto’ exhibition, held in Bangkok in March 1997, Itō Tāri performed Self-portrait 1996 (Jigazō 1996自画像), in which she looked at her own sexuality as a lesbian. At ‘Womanifesto II’ in March 1999, she performed Me Being Me (Watashi o ikirukoto 私を生きること) at Saranrom Park in Bangkok. Itō Tāri's message as she came out as a lesbian, exposing her own sexuality and body, made a strong impression on the audience at Womanifesto.

It was at these two initial editions of ‘Womanifesto’ that Itō Tāri either met again or met for the first time Amanda Heng, Arahmaiani, Nilofer Akmut, Varsha Nair and Nitaya Ueareeworakul. These connections later led to the important exhibition, curated by Itō Tāri, ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ (Ekkyôsuru onnatachi 21 越境する女たち21) in Japan in 2001. I have been following Itō Tāri's performances and activities since the mid-1990s and formed similar connections when I participated in the third Womanifesto project in 2001 as an observer.

My purpose in writing this paper is to identify the mutually influential relationship between Itō Tāri and the early Womanifesto. To this end, I will first review the performance works she presented as part of ‘Womanifesto I’ (1997) and ‘Womanifesto II’ (1999), followed by a brief introduction to her life. I will then discuss the Japanese women artists’ group WAN (Women’s Art Network), which Itō Tāri founded, and ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’, which WAN organised in Tokyo and Osaka in 2001. Finally, as an epilogue, I will recount my own experience at the Womanifesto 2001 Workshop, where I was invited as a researcher and participant. In this way, I will clarify what kind of network Itō Tāri was building, with whom she was trying to connect, and how she pursued these connections between the late 1990s and the early 2000s. I will also examine how the methodology and spirit of Womanifesto influenced the movements of women artists in Japan. To support this analysis, I will refer to Itō Tāri’s performance recordings, various historical materials, and her words. Her 2012 autobiography Move: Ito Tari’s Performance Art (Mûbu: aru pafômansu âtisuto no baai ムーヴ:あるパフォーマンスアーティストの場合 ) is especially significant in this regard.2

It has already been four years since Itō Tāri passed away. One year after her passing, in September 2022, an exhibition and screening were held in her memory in Koganei City in Tokyo, where she lived for the final years of her life.3 Her friends and family, including myself, have been left with a vast amount of artefacts, including catalogues of exhibitions she participated in, books on art and theatre in Japan and abroad that she had collected and read since her youth, video recordings of her performances, letters, notes, and flyers. We are in the process of organising these items for public viewing and this paper adds to these efforts to historicise Itō Tāri’s life and practice.

Itō Tāri’s activities in Womanifesto (1997 & 1999)

1) Self-portrait 1996 at ‘Womanifesto I’, 1997

Itō Tāri participated in Womanifesto for the first time in 1997 and the second time in 1999. Both were important early years of the Womanifesto movement, which at the time centred around women artists based in Bangkok. ‘Womanifesto I’ was held at Bangkok’s Concrete House and Baan Chao Phraya Gallery in 1997. The exhibition included eighteen artists and Itō Tāri gave the performance Self-portrait 1996 to celebrate International Women’s Day. In her autobiography, Move, Itō Tāri introduces ‘Womanifesto I’ as follows:

In 97 and 99 I participated in Womanifesto, an international women artists exhibition started by the Thai artist Nitaya Uea-reeworankul [sic] in Bangkok. Womanifesto combines the words woman and manifesto. Many exhibits around the world were exploring gender more directly, but Womanifesto was organized by women artists themselves, without relying on curators. ...Noe Jantawipa of Empower Foundation, a group working on AIDS Education, and Somporn Rodboon, Professor of Art History […] helped with the next exhibit in 1997.4

At the end of the 1990s, when Itō Tāri joined the group, and in 2012, when this autobiography was published, Womanifesto's activities were little known among art professionals in Japan, and even now are only known to those interested in feminism and Asian art and activism. This is due in part to the Japanese art world’s indifference to and prejudice against feminism in Asia.

It is noteworthy that ‘Womanifesto I’ involved as an advisor Somporn Rodboon, a field-leading art historian and curator in Thailand. As is well known, Somporn Rodboon has played an important role in introducing contemporary Thai artists to international exhibitions such as the Asia Pacific Triennial (Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, 1993–) and the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale (Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, 1999–2014). The participants of ‘Womanifesto I’ were helped by Rodboon's deep insight and her international perspective from a woman’s point of view. The organisational form and methodology of Womanifesto, which Itō Tāri was attracted to because it was ‘organised by women artists themselves, without relying on curators’, later served as a model for the ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ exhibition that she organised. Itō Tāri’s reflection continues with the following description of ‘Womanifesto I’:

The venue was Concrete House, where Noe’s partner and performance artist Chumpol [sic] Apisuk was based. The three-story building was not fancy which was perfect for performance art. We could do whatever we wanted. At this event I met Amanda Heng, Arahmaiani, Nilofar Akmut, Varsha Nair and Nitaya [Ueareeworakul]. It was my first experience to work with Asian performance artists. Later, we asked these artists to participate in Women Breaking Boundaries 21.5

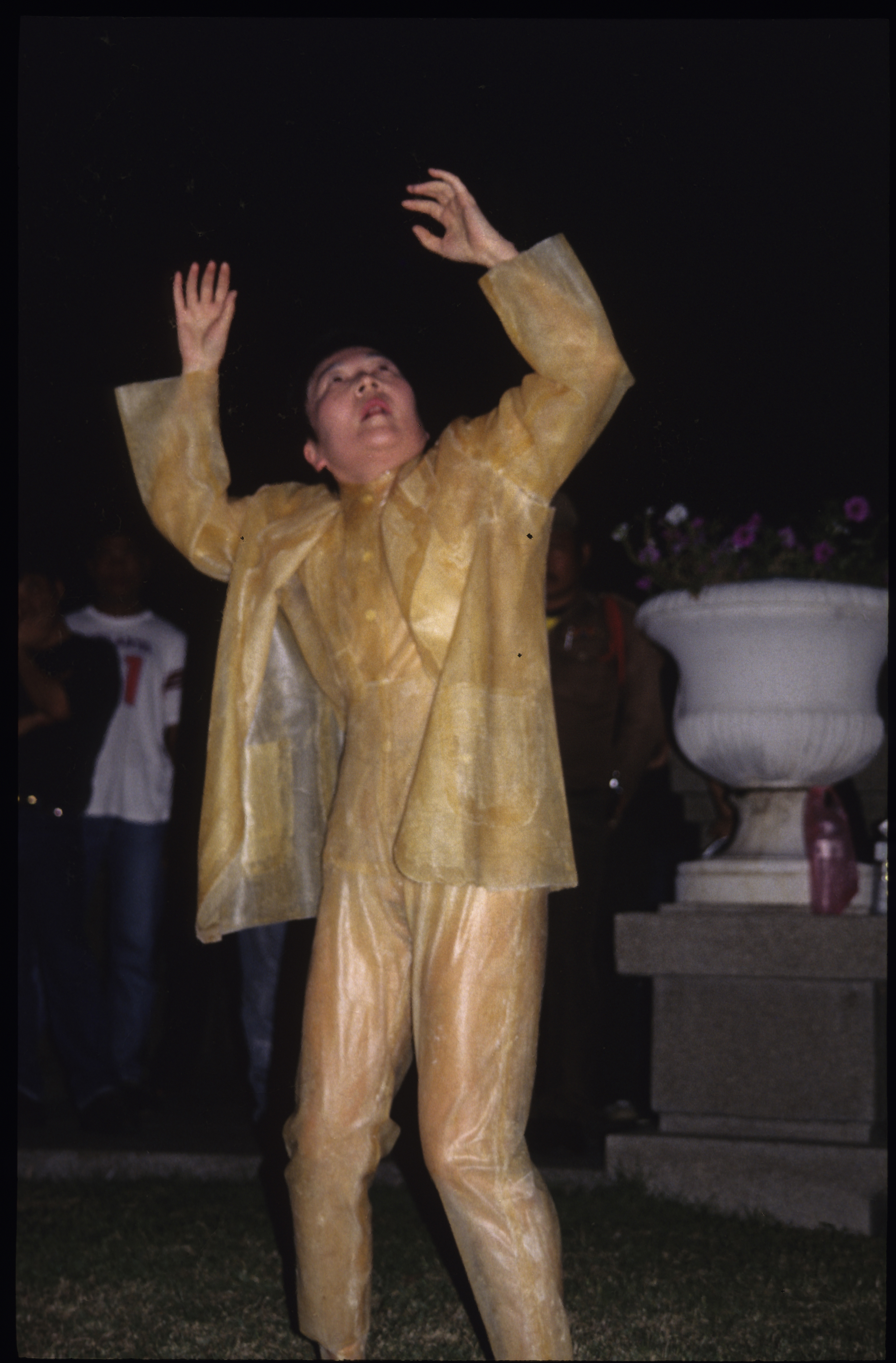

Itō Tāri performed Self-portrait 1996 on March 8, 1997, International Women's Day, in a small room in Baan Chao Phraya, Bangkok. Standing in front of a large hanging cloth that was painted to depict female genitalia, Itō Tāri breathed into a tube which was connected to a second skin made of latex rubber that clung tightly to her body. As if to challenge ableist norms, or the hetero male gaze that admires only parts of the female body such as breasts and buttocks, unexpected bulges appeared here and there on Itō Tāri’s body, each inflated to the point of popping. The performance lasted an hour in front of a packed house.

The Bangkok Post reported at the time that the work was ‘the most impressive’ and ‘the best performance art seen by this reporter in Bangkok’.6 The Thailand Times, after describing Itō Tāri’s performance in detail, wrote, ‘the work is seen as a radical turning point in attitudes about women and sex in Thailand; a staunchly Buddhist country’.7 According to [NAME], the work was considered effective because ‘from the initial shock, the audience reaction began to change to fascination and the recognition that women should not be afraid or ashamed of their bodies’.

What kind of work was Self-portrait 1996 that it shocked and shifted the perspectives of audiences, such as those in a staunchly Buddhist country like Thailand? The ‘initial shock’ referred to in Bangkok was in fact not in response to the bursting of the artist’s bodily bulges, but rather to her coming out as a lesbian. The Womanifesto performance was part of a series of Self-portrait works Itō Tāri began in 1996 in which, once deflated and seated, she would repeatedly ask herself: ‘Who are you?’ To this question, she would respond alternately with her name, occupation, nationality, age, and by stating that she was not married. The same question and answers were then repeated at varying paces and intensities for around ten minutes until, at the end, Itō Tāri replied with ‘I am a lesbian. I am a lesbian who loves women’. For Itō Tāri, her Self-portrait series was ‘a statement of one's sexual identity, an affirmation and sharing of female sexuality, and an interrogation of the body’.8

Although seeing an artist come out in this way—by explicitly stating their lesbian sexuality within their own artwork—was a new occurrence in Japan, the mainstream art world ignored or was indifferent to it.9 Furthermore, when Itō Tāri performed at public women’s centres, she was not allowed to use the word ‘lesbian’. By the 1990s, queer cultural activities had become more prevalent in Japan, with events such as lesbian and gay parades and queer film festivals emerging, but despite this, homophobic consciousness remained strong in society, and lesbians were pushed into an even more invisible existence than gays. Itō Tāri‘s experience of having her identity rejected by public institutions, even though her work was accepted by audiences, changed her view of art. She started to think that ‘it is part of the work of art to convey a message’. Itō Tāri subsequently performed her Self-portrait in twenty-six different locations—not only in Japan but also in other parts of the world—making it an epoch-making work for both the artist herself and the places it was performed.

2) Me Being Me at ‘Womanifesto II’, 1999

Itō Tāri wrote down her memories of ‘Womanifesto II’, which was held in Bangkok from March to April 1999. It is a little long, but let me quote from it:

Because of the success of the first event, there was support from the city, and it was much bigger. 34 [sic] artists—twice as many as before—participated, and the park was filled with installations. Marathon runners, Tai Chi groups, children playing, salarymen, old women chatting were there as usual.

We would go back to Nitaya’s house to get away from the bustling city and cool off by the waterway between her kitchen and dining room. After a wash in the bathroom we would sit in the open rooms, feel the breeze blow through the house, and forget the burning heat. We talked for hours day after day. Many activist projects in southeast Asia were born out of these passionate conversations at Womanifesto.10

For this edition of Womanifesto, Itō Tāri performed Me Being Me in Saranrom Park, next to Wat Pho Temple, in the middle of Bangkok. According to the artist’s own concept of the work, she is indeed very clear on her aim: ‘Everybody should be able to live their own lives. My work explores the body and eroticism of a single woman in the face of sexual discrimination and heterosexuality, aiming to create a universal expression.’11

The Womanifesto Archive at Asia Art Archive has many photographs of Itō Tāri’s performance at that time. In one photo, she and Amanda Heng are preparing for the performance in Saranrom Park. In other photos, women are sewing a large handmade vagina sculpture that then hangs from a tree next to balls of string, and elsewhere we see the artist handling balls of red wool, which she has then unravelled and which finally hang as loose threads in front of the hanging vagina. In one image, Itō Tāri stands behind her gigantic vulva sculpture, her head protruding from an opening at the top. Seeing this also reminded me of the work (1989) by Shawna Dempsey, a Canadian performance artist with whom Tari had been in contact.12

The first performance of Itō Tāri’s Watashi o ikirukoto (Me Being Me) took place a few months before ‘Womanifesto II’, in November 1998, as part of the exhibition ‘Ravuzu bodei: nûdo shashin no kingendai’ (‘Love’s Body: Rethinking Naked and Nude in Photography’), curated by Kasahara Michiko. Kasahara, then a curator at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, had been introducing new perspectives on gender and sexuality through photography since the early 1990s. Prior to 'Love’s Body', Kasahara organised key exhibitions such as: ‘Watashi toiu michi ni mukatte: gendai josei serufupôtoreito’ (‘Exploring the Unknown Self: Self-portraits of Contemporary Women’) in 1991, and ‘Jendâ: kioku no fuchi kara’ (‘Gender: Beyond Memory, the Works of Contemporary Women Artists’ in 1996. As part of this lineage, ‘Love's Body’, and therefore Itō Tāri’s performance of Me Being Me, drew the attention of many feminists in Tokyo ahead of its presentation at ‘Womanifesto II’ in Bangkok.

Despite the two distinct moments of connection with Womanifesto in 1996 and 1999, Itō Tāri had in fact become acquainted with the budding movement of Womanifesto at numerous events held earlier in Japan. In March 1996 Itō Tāri had performed Self-portrait in the 3rd Nippon International Performance Art Festival (NIPAF), held in Tokyo and Nagano Prefecture. Impactful photographs of Self-portrait taken by Shibata Ayano catapulted the work into fame and have been featured in various media since then. The 3rd NIPAF was also attended by artists with whom Itō Tāri had deep connections, including Amanda Heng, Chumpon Apisuk and Martha Wilson. For the NIPAF catalogue, Apisuk wrote about the ‘Tradisexion’ exhibition that was held at the Concrete House in Bangkok the previous year and the performances the women artists presented for International Women’s Day, so naturally Itō Tāri must have been aware of Womanifesto’s emergence. In 1998, the 5th NIPAF was attended by Arahmaiani, although Itō Tāri did not participate. It was through such connections, and the two Womanifesto exhibitions that followed, that Itō Tāri drew inspiration from Womanifesto’s artist-led, curator-free model of collective organising. At a time when she was frustrated by the male dominance over Japan’s performance scene, Womanifesto‘s network and approach can be read as influential on how Itō Tāri organised and practiced in Japan.

The life and artistic activities of Itō Tāri

1) Choosing art that involves the body

What kind of life did Itō Tāri lead, and what kind of art activities did she engage in?13 It was as a student at Wako University’s Department of Arts in Tokyo that Itō Tāri made the decision to become an artist. Arriving in 1969, she participated in the student movement and the anti–Vietnam War movement. In a university seminar she learned about Russian Constructivism, and she was fascinated by the spectacle of theatre and the close-up world of the body. Then she chose to express herself not through painting but through her body. From 1973, she studied the basics of mime at Namiki Takao’s physical training class, and also studied under butoh dancer Ohno Kazuo (1906–2010).

It was when Itō Tāri was at the age of 31, while searching for her own expression through trial and error, that she came to a major turning point. She visited the Netherlands in 1982 and took lessons at Theatre Het Klein in Eindhoven, directed by Halina Witek, later signing an exclusive contract to perform her own works throughout the country. After her contract with Het Klein ended in September 1983, Itō Tāri moved to Amsterdam, where she continued to perform independently. During her four-year stay in the Netherlands she experienced a style of pantomime that pushed her far outside of the conventional conception of what a mime was supposed to be. The creative environment was also fresh and therefore richer than anything she could have imagined at the time in Japan.

By the time Itō Tāri returned to Japan in 1986, ‘performance art’ had taken off. She observed that ‘people in music, art, dance, theatre, film and criticism were all coming together to explore new ways of expression including lots of experiments with “the body”’.14 Itō Tāri was an active participant in those events, though now emphasising ‘doing’ rather than pantomime or dancing. Furthermore, she was interested in the concept of an ‘epidermis’—the boundary that separates the inside from the outside—and found the potential for latex rubber material to operate as ‘another skin’. In this way, Itō Tāri established her own artform: bringing her broadened horizons from the Netherlands to a newly interdisciplinary and experimental Japan.

In 1990, the Tajima Performance Festival was held at the site of a former copper mine and atthe last remaining wooden school building in a ghost town in Fukushima Prefecture. Itō Tāri was responsible for recruiting international participants for the festival and invited Canadian performance artist Randy Anderson, among others. In the same year, after embarking on a nine-city tour across Canada, Itō Tāri came out as a lesbian to her parents and family. Around this time, she also participated in AFA (Asian Feminist Art) forum and travelled to Indonesia, Thailand and Hong Kong, gaining a firsthand understanding of the history of, and poverty across, Asia. Her works in these parts of the world, including guerrilla performances on racial themes, enabled Itō Tāri to accumulate a wealth of experience.

If the 1970s defined Itō Tāri’s path and the 1980s opened it up, then it was from these contexts that she would go on in the following decade to create her epoch-making works: Self-portrait in 1996; and Me Being Me in 1998.

2) Supporting and Connecting Women Artists: ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ Exhibition and WAN

In the 1990s Itō Tāri was involved in Japanese performance events, but at the same time questioned their male-centredness. She recounted this time in an article she wrote in 2000:When I returned to Japan, I began to organise festivals and events with my friends to perform. However, most of the people around me were men, and things were inevitably done according to their manners and way of thinking, which left me feeling unsatisfied despite my best efforts. I began to think that there should be a way to do things in a way that feels right without overstraining. My desire to see things from a woman’s point of view and to express myself from that point of view grew.15 In addition to these desires, Itō Tāri did not want to be confined to being an artist who only made performances. Therefore, in 1994, she started WAN (Women's Art Network), a network for women artists, but, having started it on her own, it did not lead to as many connections or expand as she had hoped. Then in December 1997, after participating in ‘Womanifesto I’, Itō Tāri called on Japanese women to relaunch WAN. They discussed again and again what they wanted to do, why women's art, and who ‘a woman’ is.

WAN defined their organisation as follows:

'WAN is a group which:

- creates an environment in which women can freely create what they desire;

- sees cooperation between professionals and amateurs;

- plans interaction between creators and viewers instead of hiding away inside a group consisting solely of artists; and

- gathers materials and provides information about women artists past and present.’16

The network of women who came together in sympathy with these aims grew, and with Itō Tāri at the centre, they began working to organise an exhibition. This resulted in the ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ exhibition, held at the Hillside Forum in Tokyo from 17–28 January 2001.

‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ was a complex project consisting of not only an exhibition, but also talks by senior female artists, a symposium and performances.17 Among the forty participating artists were six invited from abroad (Amanda Heng, Arahmaiani, Nilofar Akmut, Nitaya Ueareeworakul, Varsha Nair, and Shu Lea Cheang). When we look at the list of invited international artists, it is clear how important the network established by Womanifesto was; what is also evident is the inspiration Itō Tāri gained from their methodologies. Artists were invited to participate regardless of whether they were professionals or amateurs, and the exhibition was organised without a curator. This was also to reconsider the position of women artists who were marginalised as ‘amateurs’. In this way, the exhibition formed a new network of women artists.

At the Women Breaking Boundaries 21 exhibition, Itō Tāri premiered her performance Osore wa doko ni aru? (Where is the Fear?). ‘Fear’ can be interpreted here in various ways, such as the fear and prejudice that society has against sexual minorities, the fear of the existence of diverse people and the fear of those who come out. Through her work, Itō Tāri criticised remarks by Ishihara Shintaro (1932–2022), then Governor of Tokyo, who openly made homophobic statements that ignored the human rights of homosexuals.18 During Itō Tāri’s performance, the audience wore identical white masks and photographs were taken of them that were immediately projected onto a screen. Participants experienced what it means to live as a minority ‘wearing a mask’ in public, finding themselves gazing at their own images projected among pink triangles and alongside Governor Ishihara‘s discriminatory comments.

The encounters with the international artists at ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ and their works left a deep impression on the Japanese audiences. For example, Amanda Heng from Singapore performed Women, beauty and truth.19 Surrounded by advertisements for cosmetic surgery and makeup products, Heng put an old, wrinkled bank note in her mouth, chewed it, and swallowed it. In her clear depiction of the complicity between capital and beauty, Heng attempted to resist and her work threw a question to the audience: By forcing beauty upon women, how much suffering have women endured, and who profits from it? Arahmaiani, from Indonesia, also used her own body to express anger at violence against women and their sexual exploitation, writing words such as ‘DOMINATION’, ‘EXPLOITATION’ and ‘ABUSE OF POWER’ on her body in her performance His-story III-2001 (Rekishi (kare no monogatari)). Nilofar Akmut from Pakistan gave a performance of Nuclear, Nuclear (Kaku, Kaku), which told of nuclear anxiety. Other works presented then included Mind’s journey of the landless woman (Tochi no nai onna no kokoro no tabi), an installation by Nitaya Ueareeworakul from Thailand, and Space (Supêsu), by Varsha Nair from India. Through the efforts of WAN, women who lived in Japan were able to experience and discuss their works in the context and presence of their international peers for the first time.

Later, Japanese feminist artists and scholars who deepened their mutual connections with their South Korean counterparts through ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ actively promoted exchanges with South Korea.20 In June 2002, Itō Tāri was invited to the exhibition ‘East Asian Women and Herstories‘ held in Seoul, South Korea, where she performed Where is the Fear? at the opening of the exhibition.21

Furthermore, in August of the same year, the Japan & Korea Artists’ Exchange Tour was organised under the leadership of Itō Tāri, bringing dozens of feminists, including me, from Japan to South Korea for a two-day art exchange event between the two countries. We were hosted by FAN (Feminist Artist Network) and the event was held at SSamzie Space in Seoul, an experimental alternative space that was then run by Kim Hong-hee, a leading figure in feminism and contemporary art and now director of Seoul Museum of Art.

While Itō Tāri was in Seoul, she was also invited to perform along with another performance artist, Takahashi Fumiko, at the fourth anniversary of the House of Sharing (Nanum-ui jib), a nursing home for ‘comfort women’ survivors that includes The Museum of Sexual Slavery by Japanese Military, an exhibition space dedicated to their stories. In her haste, however, Itō Tāri brought two pairs of pants to the venue, mistaking the top and bottom parts of her outfit for the performance. With quick wit, she split the crotch of one of the trousers and put it over her head to make a top. Part way through the performance, her makeshift top tore in the middle, baring the upper part of her body, and yet she continued to perform. A halmǒni, Kim Soon-duk (1921–2004), who had been a Japanese military ‘comfort woman’ and painted about her experience, saw this performance and later told Itō: ‘You want to peel away your shell, just like peeling off the skin of an onion.’22

Kim’s words resonated with Itō Tāri as a reminder of the resentment felt by lesbians who are ignored no matter how many times they come out. Here she observed a similar lack of recognition taking place in response to the coming out of other oppressed people—in particular of those Japanese military ‘comfort women’ whose demands for an apology and reparations from the Japanese government do not get through, no matter how many times they appeal. Their encounter at this time would give birth to Itō Tāri’s work I will not forget you (Anata o wasurenai) (2005), in which, while actually peeling an onion, Itō Tāri mourned Kim’s death. Later, in 2007, Itō Tāri would also visit Sakima Art Museum in Okinawa to perform and learn of the realities around the U.S. military bases and sexual violence in the region, leading to the creation of her One Response series (2008–13, 18).

In the year after Itō Tāri’s return from South Korea, she decided to leave WAN (which continued until 2008) in order to move onto other community-building activities. Back in 2001, after the ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ exhibition concluded, Itō Tāri had told me and others that she felt as if she had completed her role. When she left WAN in 2003 it was to start PA/F SPACE (Performance Art / Feminist Space) in Tokyo, where she created a strong base for the lesbian community. She was also a founding member of the group FAAB: Feminist Art Action Brigade, but the group was short-lived, operating from 2002 until they held the ‘Borderline Cases’ exhibition in 2004. Over this period, Itō Tāri continued with her anti-war activities on the street as part of the international peace network Women in Black23, through which she persisted in bringing attention to such issues as Japanese military ‘comfort women’, US military bases in Okinawa, radioactive contamination in Fukushima and censorship in Japan. In recognition of these activities, she was awarded the Yayori Journalist Award at the 2011 Women’s Human Rights Activities Awards. Matsui Yayori (1934–2002) was a journalist and social activist devoted to women’s rights and peace who rallied international advocates in the Violence Against Women in War Network to organise the Tokyo Women’s War Crimes Tribunal in 2000.24

Itō Tāri continued to pursue women-centred projects and political themes, including the 2012 exhibition ‘Women In-Between: Asian Women Artists, 1984–2012’ (‘Ajia o tsunagu: kyôkai o ikiru 1984–2012’), which was curated by women and toured Japan. The exhibition featured performances by Itō Tāri again addressing the themes of radioactive contamination and Japanese military ‘comfort women’. However, around this time—also the time of the publication of her autobiography MOVE—Itō Tāri gradually began to lose her physical mobility. She developed ALS at the age of sixty. Itō Tāri suspended her performance activities for a while, but in 2019 she successfully gave performances of Before the 37 Trillion Pieces Get to Sleep (37 chôko ga nemuri ni tsuku maeni) in collaboration with her caregivers in Tokyo and Vancouver. Thirty-seven trillion is the number of cells in a human being. In the summer of 2020, Itō Tāri reported that she ‘had lost the use of her lower limbs, could extend her upper limbs only up to 30 cm away from her body, could type only with one finger on the keyboard and could not move her trunk or hips from side to side’.25

On April 11, 2021, Itō Tāri gave a private performance of Before the 37 Trillion Pieces Get to Sleep vol. 2: When I rub my own forehead (Sanjuu-nana chōko ga nemuri ni tsuku mae ni: Jibun de hitai o naderu toki 37兆個が眠りに就くまえにvol2:自分で額を撫でるとき) at Art Gallery Chika in Tokyo. It became her last performance.26 This performance continued Itō Tāri‘s critique of issues of sexuality, Japanese military ‘comfort women’, radioactive contamination in Fukushima and U.S. military bases in Okinawa, all of which was layered within the poetry of her everyday life, lived desperately in the midst of rapidly progressing ALS. I will never forget Itō Tāri’s figure and voice continuing to create new forms of expression as she stood in an intersectional space of multiple layers and complexities.

Epilogue: My Participation in Womanifesto Workshop (2001) and what Itō Tāri left behind

Let me return here to Womanifesto and Itō Tāri.

My own connection with Womanifesto began was when I was invited to the Womanifesto Workshop. It was in 2001, and eighteen professional women artists, curators and arts administrators including five student volunteers from all over Asia were invited to a 10-day workshop with the local people and event organisers at Boon Bandaan Farm in Sisaket, in the Isan region near the Thailand–Cambodia border. I was told that Womanifesto would pay for all my transportation and accommodations within Thailand, while I would have to pay for my own travel to Thailand. It was a dream come true for me to spend days from morning ’til night talking, playing, eating, and working with the participating artists and people.

This was more than two decades ago, so my memory may be a little faulty. I recall that I joined the event at the end of October, a few days late because I had university work to attend to. A number of accommodation huts and facilities had been built for us participants, each of different sizes and shapes, using traditional construction methods. I stayed alone in one of the small huts. The artists were supported not only to create artworks, but also to think together about the position of women living in rural Thailand and how they pass on their wisdom. We were very busy day after day, participating in activities including workshops to learn crafts such as basket–making and weaving from local artisans. I can’t forget the melodies of the Thai folk music that played as we danced in the evening.27 It was an event that involved the whole local community.

During the workshop, artists’ works were introduced by their creators to the participants and there were also exchanges through performances. These were very effective as an opportunity to interact and think about the meaning of each other’s work. However, it was not a ‘comfortable’ environment like a hotel in the city. Every night in bed, everyone was plagued by large ants, and whatever medicine we applied did not soothe the stings. Some participants were stung by scorpions. It also wasn’t easy. Washing my face and body with rainwater scooped from an earthenware pot in the doorway of the hut was an experience. The ‘floating game’—a dangerous game in which one floats in the river on one’s back and is swept away by the current—for which I joined the artists in the muddy orange-coloured river, was also great fun.28 Including these challenges, it was a precious experience for me to be allowed to see many things. The project did not stop even after we went back to Bangkok, as we continued our discussions.

One thing that left a strong impression on me at the residency was the Thai food that was prepared for us every morning. On the farm, when we woke up, a variety of dishes were already laid out on the table, and we were free to eat whatever we liked. The taste of the food was far superior to any other Thai food I’d ever had. It was as if my body was being overcome with unknown flavours from all directions.

Inoue Hiroko, a participating artist from Japan, spent every morning in the main house watching and listening to the local people cooking these delicious dishes. Inoue painted ashes over the twenty-four jars she’d purchased locally and in them sunk photographs of people who told her their stories (for the installation Closing Eyes, 2001).29 When they were asked ‘What is your dream?’, almost all of them talked about their families. Inoue, who had been photographing the windows of a mental hospital for a long time, then asked the people who worked on the farm, ‘What do you feel from the windows?’. The answer that came back was ‘The windows are a wonderful thing that is connected to the outside world.’ Surprised that the local people talked about their dreams so concretely, Inoue turned her attention back to her own life and asked herself what kind of life she was leading. Such was the personal impact of those ten days for many of the artists.

More than twenty years have passed since I participated in Womanifesto 2001. On the one hand, in Japan today the conservative government has doubled military spending, cut off the vulnerable, and censorship is rampant in the art world. On the other, however, a number of art groups that are interested in and active on gender issues are emerging, one after another. Prominent among them are the Tomorrow Girls Troop (Ashita shôjotai), inspired by the Guerrilla Girls and formed in 2015, who fight against inequality in the art world, and the organisation Hyogen no Genba Chosadan fields(Investigating Discrimination, Harassment, and Inequality in the Arts, IDHIA),, which formed in 2020.30 The latter investigates and provides numerical data on the reality of male-dominated structures and harassment in art, theatre, music, film, and art-related universities. Thus, the group is actively working to eliminate inequalities in creative fields and to create a place for expression that is free of harassment. Wanting to contribute even a little to this end, I also started the Feminism & Art Research Project with my colleagues in 2021.

Soon after Itō Tāri’s death, the Tari Society (Tari-no-kai) was formed to carry on her legacy. The group held a series of seminars in 2023 entitled ‘Remembering Ito Tari: Art, Sexuality, and Independent Living’ (‘Ito Tari o kiokusuru: Âto, sekushuariti, jiritsu seikatsu’).31 As the subtitle of the seminar indicates, art, sexuality, and life after the onset of ALS are the three pillars of Itō Tāri’s activities and life. When we reflect on her life, none of these elements can be separated. Itō Tāri has always been conscious of the intersectional structure of things, of making invisible beings visible through her performances.

While Itō Tāri’s performances at home in Japan have been revisited, her activities abroad have not yet been fully investigated, and this is a work that needs to be done in the future. In this paper, I have established that Womanifesto was a major influence on Itō Tāri’s activities from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, seen both in her network and in her methodology. How, then, can Itō Tāri be placed within mainstream performance history or art history? It is difficult to find a definitive place for Itō Tāri, who had many connections with Eastern Europe, Canada and various parts of Asia, within the pre-existing historical narratives that are centered on the West.

Just as Itō Tāri’s performances questioned and changed the existing frameworks of mime and performance art, her networking and advocacy work questioned social boundaries. While coming out as a lesbian and creating networks of women artists, she always tried to fundamentally question ‘Who is a woman?’. She recalls that at one point in the early days of WAN, when someone with a ‘male’ voice called and asked if they could join, the members discussed it and decided that ‘women who want to solve women's problems’ could become members. Itō Tāri tried to respond to this difficult issue expressively through her practice, first with the question, ‘Who is a woman?’, and then, asking who is ‘the woman who manifests’?32 In her work, Itō Tāri recognised that the dualism of men and women cannot solve such problems.

Itō Tāri always expressed sympathy and solidarity with other minorities and campaigned assiduously against war and censorship. When illness prevented her from going out, she did not suffer in silence from the unreasonableness of the welfare administration but appealed to the local government to improve the situation. The ‘care’ she sought to address her social isolation not only revealed the flaws in the system, but also questioned the Western concept of ‘independence’. Even then, Itō Tāri thrusted a question at us: ‘How do we live?’. She was always ahead of her time and ran through her life. As Itō Tāri said:

‘Performance art is expressed to the people who are living. For this reason, it is a radical art form and at times it is a fight.’33

1 Born as Itō Sawako [CHECK RE REFERENCES TO ‘Miwako’], the artist later adopted Itō Tāri as a combined artistic name. She has also been professionally referred to as Tāri Itō, including during her engagements with Womanifesto. She is referred to by an abbreviated form of her professional name, Tāri, in this piece.

2 Tari Ito, Move: Ito Tari’s Performance Art, (translated by Rebecca Jennison, Japanese / English, Impact Publisher; Tokyo, 2012. Also, a video archive collection is available: ‘archive: Ito Tari’ in IPAMIA (Independent Performance Artists’ Moving Images Archive), https://ipamia.net/tari-ito/ Interviews by KITAHARA Megumi, ‘Watashi o ikiru koto’ in Kakuran bunshi@kyōkai: Āto akutivizumu II (‘Me Being Me’ in Molecules@Boundaries: Art Activism II), Tokyo: Inpakuto shuppankai, 2000. For other articles and interviews of Tari Ito that Kitahara published since 1990s, see respective notes in this paper.

3 KITAHARA Megumi 2022, ‘Itô Târi ga nokoshita mono: Tuitô tenjikai hôkokuki (What Ito Tari left behind: a report on the memorial exhibition)’ in Etosetora: Femimagajin (etc.: Feminist Magazine), vol.8, Tokyo; etc. books, 2022.

4 Itō Tāri, Move, p. 91. Author’s notes: Foundation is a non-profit organisation in Thailand for the support of sex workers with education, counselling, and advocacy, and its work continues today.

5 Ibid., p. 91.

6 See Foon, ‘Womanifesto’, Bangkok Post, March 8th, 1997.

7 Kunanant Saeng-artith,’Tari Ito and the Courage Behind Womanifesto’, Thailand Times [Entertainment Times], Vol. 4, Issue No. 1228, March 12th, 1997.

8 Ito Tari, ‘Pafômansu ‘jigazô 1996’ no shûhen (Around the Performance, ‘Self-portrait 1996’)’, Theater Arts Shiatâ âtsu, vol. 7, Tokyo; Bansei-Shobo, January 1997, p. 128.

9 While other Japanese artists, such as Sadao Hasegawa (1945–1999), had publicly identified as queer before this time, and the artist and founding member of Dumb Type collective Furuhashi Teiji (古橋悌二) publicly came out as gay and HIV positive during a multimedia performance in 1994, lesbianism was still relatively invisible within society and Itō Tāri broke new ground with Self-portrait when she came out as a lesbian within her own work.

10 Opcit., Itō, Move, p. 90. Author’s correction: there were 32 artists in the Womanifesto II exhibition and 18 in the previous edition.

11 Tari Ito, ‘Concept,’ Womanifesto-II: The 2nd International Women's Art Exchange, (exhibition catalogue) Thailand: Womanifesto, 1999.

12 Shawna Dempsey created We're Talking Vulva,(1986/1990), a performance and later film (with Lori Millan), which tackled the vagina head-on and profoundly influenced subsequent queer/lesbian performance and visual artists. In 1996, Dempsey had performed in Japan at the Third Nippon International Performance Festival(NIPAF).

13 The following publications give summaries of Itō Tāri's work and life: Kitahara Megumi, ‘Ito Tari’, Bijutsu Techô 73 (1089) (‘Joseitachi no bijutsushi’ tokushûgô), (Bijutsu Techo: monthly art magazine, vol. 73, no. 1089, Special Issue: Women and Art History), August 2021, Tokyo; Pamela Wong, ‘Obituary: Tari Ito (1951–2021)’, Art Asia Pacific (Hong Kong; web mag.), October 21, 2021. https://artasiapacific.com/news/obituary-tari-ito-1951-2021

14 Op. cit., Ito, MOVE, p. 29.

15 Ito Tari, ‘Onna, towa dareka (Who is ‘a woman’?)’, Impaction, no. 117, Tokyo, Impact Publisher, January 2000, p. 34.

16 Megumi Kitahara, ’WAN/Women Breaking Boundaries 21 Document’, Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ Exhibition: Women’s Art Network, Dokyumento: Ekkyôsuru onnatachi 21 ten (Women Breaking Boundaries 21, exhibition catalogue, Japanese/English) Tokyo, Saiki-sha, 2021.

17 The following are available about the ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’ exhibition: Women’s Art Network, Dokyumento: Ekkyôsuru onnatachi 21 ten (Women Breaking Boundaries 21, exhibition catalog, Japanese/English) Tokyo, Saiki-sha, 2021; Desiree Lim (director), Women Breaking Boundaries, (documentary video, 85min.) 2001; and Takashi Fumiko, ‘From Within the Chaos: The Making of Women Breaking Boundaries 21 (2001)’. Bunka-Cho Art Platform Japan Translation Series, originally published as ’Konton no naka kara: Ekkyosuru onna tachi meikingu repо̄ to’, Aida, no. 62 (February 2001), p. 9–16. Translated by Monika Uchiyama. https://contents.artplatform.go.jp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/APJ202110Takahashi2001.pdf (accessed 27 September 2025).

18 Ishihara Shintaro continued to engage in hate speech against vulnerable people, including his comments against homosexuals (2010) and his statement that ALS is ‘a karmic disease = a disease that comes as a retribution for the evil deeds of their previous life’ (2020). In Japan, hate speeches and homophobic statements by Diet members and politicians continue to be rampant.

19 For more information on Amanda Heng's ‘Women, beauty, truth’ and ‘Women Breaking Boundaries 21’, see Kitahara Megumi's ‘Kôjichū nitsuki gochûi!: Ekkyôsuru onnatachi 21 ten (Attention, Under Construction: Women Breaking Boundaries 21 Exhibition)’, Impaction (serial Art Activism 32), No. 123, February 2001.

20 Exchanges between Japan and South Korea had already begun at the end of the 1990s with Japanese feminist art historians such as CHINO Kaori and WAKAKUWA Midori, who gathered at the ‘Imêji & jendâ kenkyûkai,Image & Gender Conference’. Itō Tāri also joined this study group.

21 Feminist Artist Network & Seoul Women's Foundation, The 2nd Women's Art Festival: East Asian Women and Herstories, (exhibition catalog, Korean/English) 2003. (제 2 회)여성미술제 : 동아시아 여성과 역사 : 서울여성플라자 준공기념

22 Itō Tāri recounted these words from painter and survivor Kim Soon-duk on multiple occasions, including in remarks she made in 2011 on accepting the Yayori Journalist Award at the Women's Human Rights Activities Awards. The awards ran in Japan from 2005 to 2014, and Itō Tāri's citation can be viewed via the awards' website, https://www.wfphr.org/yayori/English/award/j2011.html (accessed 28 September 2025).

23 The Women in Black movement, where women wear black clothing to protest war and advocate for peace, is active globally and in various locations across Japan, including Tokyo and Osaka. Itō Tāri was involved in the movement, created by artists, and in her PA/F SPACE , FAAB held an exhibition focused on women's anti-war activism, featuring Women in Black Tokyo alongside the Great Japan Anti-War Women in Black Organisation, in 2003. She also practiced anti-war activism by standing alone in front of train stations. Photos of Tari can be found on the following website: https://home.interlink.or.jp/~reflect/WIBTokyo/anti-warWIBorg-phots.html (accessed 28 September 2025).

24 Kitahara Megumi, ‘Hôshanô ni iro ga tsuiteinai kara ii no kamoshirenai…to fukai tamaiki…o tsuku…: Ito Tari ni kiku (I guess it's better that radiation doesn’t have color: Interview with Tari Ito)’, (Art Activism 65), Impaction, no. 183, January 2012.

25 Itō Tāri, ‘Watashi no kotoba o.’ (My Words.) vol. 1, Love Piece Club (web magazine) 2020. https://www.lovepiececlub.com/column/15028.html

26 For Tari Ito's last performance, see Kitahara Megumi, ‘Itô Târi no shinsaku pafômansu: jibun de hitai o naderu toki’ (Tari Ito's new performance: When I rub my own forehead), People's Plan, vol. 92, 2021. A video of her last performance with English subtitles was made available by Tari-no-kai (Tari Society): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Dbt2vuDhJk

27 A video on Womanifesto 2001 is available on the Womanifesto Archive: https://vimeo.com/132688087

28 Photographs (Kitahara is on the far right) from the event are available at: https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/womanifesto-archive-artists-and-projects/object/enjoy-263987

29 KITAHARA Megumi, ‘Fuzai no toiki o tsutaeru (Conveying the Breath of Absence): Interview with Hiroko Inoue’ (serial art activism 37), Impaction, No. 128, December 2001. Photographs of Inoue's work are available at: https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/womanifesto-archive-artists-and-projects/object/closing-eyes-set-of-3-photographs

https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/womanifesto-archive-artists-and-projects/object/closing-eyes-preparation-set-of-2-photographs

30 See https://ashitashoujo.com/ for ‘Ashita shôjotai Tomorrow Girls Troop’. See https://www.hyogen-genba.com/ for ‘Hyôgen-no-genba-chôsa-dan’ (Organization to investigate the scene of artistic expression).

31 For ‘Tari-no-kai’, see https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100084135446348

32 Op. cit., ‘Onna, towa dareka (Who is ‘a woman’?)’, Impaction, no. 117, p. 34.

33 Megumi Kitahara, “Itō Tāri.” Bijutsu Techō, vol. 73, no. 1089, Bijutsu Shuppan-sha: Tokyo, August 2021.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.