Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

Gaps and ambiguities in the transcript have been marked in square brackets [ ] — these will be corrected before publishing.

The following interview took place on the 5th of July 2023 between Arahmaiani and Yvonne Low.

Yvonne Low: (YL): Hello, Iani.

Arahmaiani: (A): Hello.

YL: Could you share with us how you first got to know Varsha? Nitaya?

A: Well, I think I met them when I was, having a performance in Chiang Mai. I was invited for the Chiang Mai Social Installation Festival in 1996.

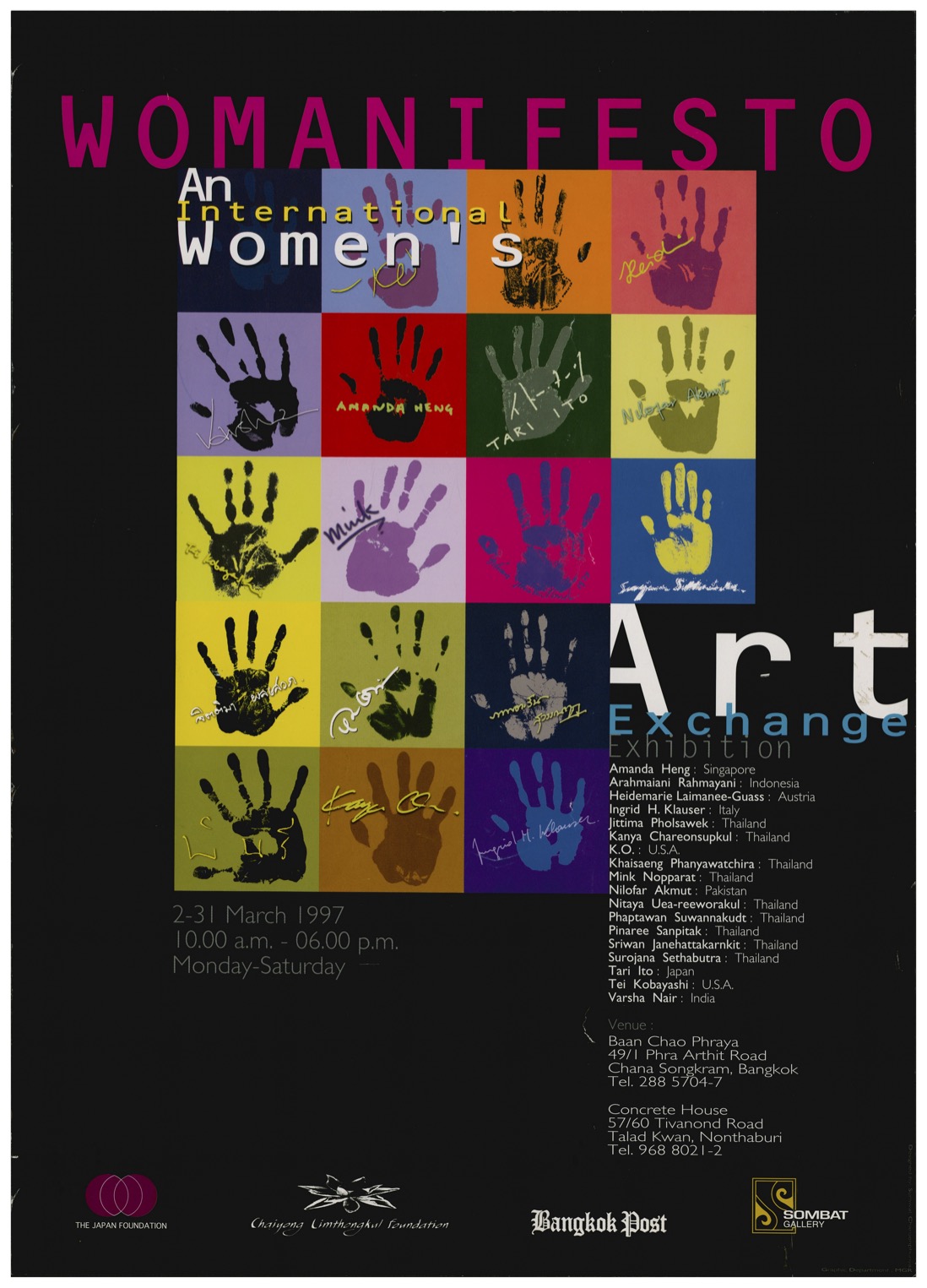

YL: So that was before. Womanifesto's first exhibition?

A: Yes, Before

YL: So, Phaptawan was there or was it just Varsha and Nitaya?

A: I don't remember exactly. I think, Varsha, was there and Nitaya, also. I think Nitaya was originally from Chiang Mai.

YL: Were they participants or part of the audience

A: I don't really remember now. You can ask them. Because, you know, as a performance artist my work was quite demanding, so I was just busy with my own preparation. Also, at the beginning of the festival, the organizers said ‘oh, yeah, sorry. You cannot do that performance.’ And I said ‘Why?!’.

He said, Navin at the time was the organizer/representative, and he said, ‘oh, no, this has to do with the sacred Buddhist area, and so you cannot perform there.’ And I said, ‘why?’, and he said ‘you don't understand. You are not Buddhist.’ And I said ‘hey, come on then, you have to explain it to me because I'm not Buddhist’.

And then finally, he took me to see the, leader of the monks and the monastery. It was interesting because when I explained my idea to the head monk, he responded really nicely. We discussed things of ours, and finally he said, go ahead, you can do it. Wow, I was like ‘Yeah!’

YL:And were there other people who had similar encounters or issues as you?

A: I don't really, remember. No, but I think my work was really controversial from the beginning. But after, I got approval from the head monk, everything was fine And I remember, at one of the sites, there were some monks attending the performance too. That was quite, inspiring also for me.

YL: And, Varsha and Nitaya, they saw this work?

A: I think so, of course. Yeah.

YL: I’m just wondering, what sort of responses they might have had. Or if you remember what sort of conversations you guys had around the work.

A: Yeah, later on when I got to know Varsha and Nitaya, of course they wanted to know about the idea behind my work. And I said, ‘yes, this is something that has to do with problems in, the society I come from, which is, today mostly, considered to be Muslim, you know, but our cultural roots somehow connected also to Hinduism, to Buddhism, even animism’. That's why I try to connect myself to, that forgotten cultural heritage, especially before Islam. What I learned during that time is, the cultural strategy developed in Nusantara—the name of the Indonesian archipelago before it was called Indonesia—was actually something that was very human and very fair to everyone, because they can accept all people with, various cultural and religious backgrounds. That's why we have this so-called principle is called in, Sanskrit, language, [‘Bhinneka Tunggal Ika’] which means ‘unity in diversity’. Even when Indonesia was becoming independent and becoming Indonesia as it is today, Bhinneka Tunggal Ika was part of this kind of foundational philosophy, surrounding Indonesida’s independence. This is very important for me. But I also understood, since I used to study in the Netherlands, that the Dutch used to colonise Indonesia for about 300 years and I got to learn that the manuscripts and the artifacts from traditional culture had been looted by the colonialists. Even until today, they still like more than 10,000 artifacts in museums in the Netherlands. Manuscripts in particular, which are the source of knowledge, they still have hundreds of thousands, so you can imagine how people have lost the knowledge of their own cultural roots. This loss creates problems, this is also the reason why, hardline kinds of Islam or other religions, become active in Indonesia, because lots of people suffer this so-called ‘identity crisis’ because they don't know about who they are, because they are disconnected from the knowledge about their own culture and cultural roots.

YL: So that time in 1996, when you took part in the Chiang Mai Social Installation Festival, was it 1996, did you say? And that was when you left Indonesia. You were exiled because of your performance, right?

A: Yes. In 1994, I was, being accused of doing something blasphemous against Islam because of my artwork. It was the painting called Lingga-Yoni, and the installation piece called Etalase. Those works actually have to do with my understanding of this forgotten cultural heritage and colonization as well. Like I explained earlier, since my only time in art school was in the 80s, I was already questioning the situation in Indonesia which was supposed to be already independent. But at that time, we were under military regime, and it was really a dictatorship.

I really questioned the meaning of independence: ‘are we really already independent with this kind of situation?’ And at that time, I created a performance, which took place outdoors during the celebration of Indonesian Independence Day on the 17th of August in 1983. I created this artwork and performance, and you know what happened? I was, arrested and imprisoned. After that, I was kicked out from the art school. Anyway, that's the beginning of my struggle, and then in 1994, I had my solo exhibition in Jakarta at [ ] which included Lingga-Yoni and Etalase. That’s when I was being accused of doing something blasphemous, because they don't understand what I am trying to express.

With the Lingga-Yoni, I was actually trying to reconnect myself to this, so-called ‘local traditional wisdom’. The symbol of Lingga-Yoni is very important, and it is actually a very old symbol from the animistic time. The symbol is about the principle of balance, of oppositional power in nature, which is seen not as black and white, but in this wise way of looking at things, where there is a of connection between the black and white, and then thinking about how to balance it.

Similar to [ ], or in the middle East and they have this kind of understanding in Christianity the cross too. The original idea of balance between the vertical and horizontal, they contain similar ideas. But anyway, this, symbol of Lingga-Yoni is very interesting for me because with this symbol of phallus and vagina, it is also a symbol about fertility, life itself, physical, material aspects of life—which are not being seen as something, with and without value, because of this principle of balance. So the material aspect and the spiritual aspect has to be somehow seen in a balanced kind of position.

YL: So this work, it was shown in but Apinan, and then later in Global Feminisms. So they’re quite well-known, in that international sense, but at the time, were people aware of what you did?

A: I think, only some people, who are well educated and who understood this cultural root that had somehow been forgotten by most Indonesians at that time. But now there is a change because, when I had my solo exhibition at MACAN Museum in 2018, this work was exhibited, I was a little bit scared, a little bit worried, but it was all right.

Now it is even collected by the MACAN Museum, and it is on exhibition in the museum until October too, and no one is protesting—no one is getting angry with me. I think that this younger generation, they understand.

YL: What about at that time in 1996, when you were in Thailand, did you feel that it was different? It was a bit dangerous for you to be doing the old taboo in Indonesia, but then when you went to Chiang Mai or Bangkok, did you feel that there was less of that problem or did you also encountered similar challenges?

A: Well, actually, I already explained about what happened in Chaing Mai, right?

YL: Yes

A: Okay. The Monks, and the leader of this is the community of the Forest Monks was really open, he didn't see it as me doing something blasphemous. So there was a really good ideology of supporting. That support for my practice is what I need, because in I didn’t get that support in Indonesia, I got death threats, because of that kind of ideology in Indonesia. The other work, Etalase, for example, is actually my kind of critique towards the global economic system, which is capitalistic and unfair for so-called marginalized groups of people. That's why I created that piece of work, as my criticism of this capitalistic, global economic system that is unfair to minorities. So, the guys who protested the work, they misunderstood it. They didn't understand it. They just said, ‘oh, you put our Quran next to a pack of condoms, that’s blasphemous!’

And so I said, ‘okay, you don't understand, you don't get it.’ In that work I'm actually talking about and questioning how culture, beliefs or religion and spirituality — there was also Buddha statue there, but no Buddhist, protesting—why these important elements of our lives, are destined to be commodities for sale. That's my question, my protest actually.

YL: Yes, I’m wondering about the many kinds of, challenges you faced, in particular, challenges that were culturally specific or rooted in the place. For example, in this case, you faced many challenges in Indonesia, but not so many in Bangkok or Chiang Mai. However, I was curious as to whether you encountered other sorts of challenges in

in Thailand. I know that Nitaya and Varsha, as female artists in Thailand, faced these culturally specific challenges. Over the several years you lived in Thailand, did you encounter similar kinds of challenges?

A: At that time, it was fine because I was connected to a community of artists and this Apinan who supported my practice. And then some of the community of artists from, Bangkok and also from Chiang Mai. And then these forest Monks also, they supported me, so I didn't really have a problem.

I stayed there for about two years, and then in 1998 I decided to return back to Indonesia because of the political problems in Indonesia at that time. I returned to Indonesia and worked in Jakarta and then, right on my birthday in 1998, the military regime fell. That was the best kind of birthday gift I have received in my life. So, in Thailand, I didn't really have any problems. Actually, what was positive is that I got support, from activists, community activists too

YL: What type of activists?

A: Woman activists, of course, and the ones who supported me the best were Womanifesto.

YL: So, you attended the first Womanifesto exhibition, you were there the whole time?

A: Yes, the first one, I was part of it.

YL: Were you involved in any of the meetings?

A: Oh, yeah. Because at that time I was staying at Varsha's apartment.

So we discussed a lot of things, every moment of every day, with Nitya too and then with Phaptawan.

YL: Phaptawan was probably in Sydney then. Right? I think she left.

A: Oh, yeah. And then after that, because she got married, right? And then left for, Australia.

YL: So I think quite a lot of things were happening then, there was Mega city there was Womanifesto. Could you share a little bit of how curating a show with Varsha came about?

A: Well, I think, at that time there was a group of women who are progressive and then, people like Apinan, you know, who supported our progressive ideas. This combined with the atmosphere in Bangkok at the time. This was, of course, connected to Chiang Mai as well, which was very lively.

This environment was very supportive of my practice too, which was really good because in my own country they see me as a weirdo, the Ideas are you seen as weird.

YL: Were you speaking primarily in English with Varsha and Nitaya too.

A: Yes, because I don't speak Thai.

YL: So in terms of your discussions, what were you guys debating about? Were there any memorable exchanges that you could share with us? Moments when you disagreed about certain things regarding feminism or certain viewpoints? Can you recall any memorable incidents that stood out to you?

A: Well actually, later on, I learned about political problems in Thailand. One problem was how the minority Muslim community has been treated unfairly, and 2005 to 2006 I worked on a program, supported by Jim Thompson.

To work with Muslim and Buddhist communities, I'm becoming like a bridge, trying to connect these two groups. My aim is to build understanding because with, political strategies that try to divide and rule people. That's usually how the elite control people, by implementing so-called divide and rule politics.

Through this project, it was called 'stitching the wounds', I tried to bring these two groups together—so they can have a dialog and communicate with each other, to reduce misunderstanding between them. It was really nice, I learned a lot also from that project.

YL: These were all community projects?

A: Yes

YL: Did you work with, any of the Womanifesto members?

A: well, of course at that time, we were already becoming a group. So, they were following what I'm doing.

YL: Sorry, what was the date?

A: The date was from 2005 to 2006.

YL: Oh, okay. So this was more recent.

A: Yes, and at the time of Womanifesto had developed further, so they were having regular events.

YL: Yes, one every two years.

A: I'm always in contact with them. So, I always inform them about my work and how it is developing.

YL: I'm really curious, how do you guys keep in touch? I mean, now we have so many ways to keep in touch.

A: Yes, yes. Now we have, whatever, social media.

YL: But back then, how do you guys keep in touch?

A: We already had phone at the time, but it was a bit expensive, and then later on there Is email.

YL: Right, okay.

A: We keep in touch with each other because we like family.

YL: That's amazing. That's very nice. Did Varsha and Nitaya visit you? Have they ever visited you in Indonesia? I know you travel a lot.

A: I don't remember if they have ever visited me, but Apinan, visited me when he was looking for me for this exhibition, The Tradition Tension. He was looking for me because I’m not easy to connect, as you know, there was no social media and I already lived like a nomad. So, it was not easy for Apinan to find me.

But finally we met in Jakarta and he told me, ‘Iani, I've been looking for you for almost a year’. And I said, ‘okay, I understand it's not easy to contact me’, but that was also my, my way of life at that time because I don't feel safe, I had to protect myself.

YL: So the mega city in 1996 was not with [AP]? No. Was with many. [You and Varsha, is it?]

A: I think so, yes. I do not remember much anymore.

YL: Yes, it's so long ago. So, I'm also very curious about risk, like just everyone's kind of reaction to the work as the audience because your work was, is very powerful. You know, you performed answers like, do not prevent the fertility of My Mind. Now we watch it in a video, but at that time it has to be this is very strong message. I'm just very curious about anything you might remember from that time, in terms of responses etc.

A: Well I sent you one video, but actually there is another, another video of, this kind of performance I will send you later on, also performed in Bangkok.

YL: Who are the audiences?

A: Well, you can see on the video, there Apinan he was still young. He was making a video actually.

YL: What did they say to you after that performance? What were the sorts of responses?

A: I actually got really good support from almost everyone, the community of artists, activists, they all supported me. That's why I was feeling relieved, because, in Indonesia I'm being seen as, there's a term actually, if you read some of the articles written by art critics, there is a term for me, ‘someone outside the fence’. [ ] in my own society. So, you can imagine my position.

YL: I mean, it is interesting that, you know, as can I guess, you an outsider in Thailand, right? But then you really feel at home there.

A: Yes. Because, when I had that discussion with the head Monk in Chiang Mai, he said ‘our way of thinking is connected’—whereas the so-called Muslim in Indonesia seems to be not as connected?

YL: Do you know that Nitaya is a Buddhist too.

A: Yeah, there's also a process of learning for me. There is something connected to Buddhism in my way of thinking. Later, when I studied in the monastery in Tibet I leaned about the heritage of Buddhism in Indonesia as well. It's very much connected, and my way of thinking is very much connected to this old ancient Buddhist philosophy. But because I am also the daughter of a religious Muslim religious leader, my late father used to be an old lama or the, an Indonesian term which is Muslim religious leader [ ]. He was also, well educated, on other cultures, his field of study was actually literature and Western culture, so got to learn about the basic principles of Islamic belief, and these principles are all very similar. These are the universal values that connect Islam, Buddhists, Hindus, whatever religion, Catholic, Christian.

I've been working with Christian and Catholic priests in Germany and I've been teaching there for more than ten years. What I learned is that the basic principles of all religion are basically the same, which is love or compassion. When you really base your lifestyle and your way of thinking on those principles you won't hate others, you won't, distrust others. But how can we live together peacefully and happily? and this is what I have learned so far, is the basic principle of all beliefs. I also realize how religion, especially after being institutionalized, can be used and manipulated for the sake of power or even for the sake of money—it is possible that that happens from time to time.

YL: So, I am trying to link this back to, not just your formative practice that took place over time, but also to 1996. There was a lot happening in 1996, and you acted on them and you were supported to act on them. The other question that I would like you to respond to is this idea of women gathering.

As you’ve been saying, people have different opinions of religion, I was also curious about different ideas and opinions on feminism. During this period, in 1996, these ideas of feminism were controversial or radical.

It is incredible to hear that you had all this support in Thailand, as if it has always been there. But I don't think it has always been there. I think people made that happen. It was through Varsha and Nitaya and others, who made that kind of support possible for other women artists. Because. obviously at that time, it you wanted to be a full-time female artist, or professional artist it's not that easy. Do you recall any of these challenges that women artists were experiencing?

A: Yes, of course, and this is still happening today. It is clear that Asian, South Southeast Asian society remains male dominated—the art world is not so different.

YL: Yeah, I was just wondering in that time when you guys got together as a female centered organization.

What sort of responses did you encounter from others? Were there, for example, women artists who didn't think that women should separate themselves from men?

A: I was only in Thailand for two years, and so, I just met all these people who supported my practice.

YL: Were they women and men?

A: Women and men. This up [ ], this community of West San moneyed and many other, yeah. Some others before my. They were all very supportive, so I didn't experience anything that was problematic.[ ]

In regard to the struggle of woman in Thailand during that time. In my own country, this not easy. Although later, when I got to learn about the traditional local wisdom, where this principle of equality was already there, because, within that kind of approach and philosophy, we are not entrapped in any material aspects. And so, when you come to a deeper understanding you don't see the physical reality, male or female, it doesn't really matter. Yeah. It is not a big deal if body is male or female— it is the spirit that matters. When I was studying in [ ] Monastery, in India, at the beginning, I was a bit confused and a little bit shocked because I was placed in the monastery of monks, not nuns. So I'm the only girl with long hair. And I didn't wear a robe. And at the beginning, I was like ‘was I a man in my past life?’ Because of course, they are talking about reincarnation and past lives. When I met a lama or old lama I asked him: ‘lama, why I'm being put in with the male monks not the nuns? Was I a man in my past life?’ The lama smiled and just said, ‘it’s simple, logical’. So I said ‘Oh, Lama please explain this to me. What does this mean? I don't really understand.’ And he said ‘What connects you with our lineage is your spirit, your way of thinking, what you are doing. It doesn't really matter what form of your body take, you can be male or female or even mixed’ he said ‘it is no problem.’ And I was like, ‘wow, great. Fantastic.’

YL: Yeah, if only the society sees it this way though.

A: Yeah. Now we live in this society being pushed towards, this kind of lifestyle which focuses on materialism, individualism—so then people are busy with the form. Oh, ‘this is the female’. If you have this female body, they are being seen as minorities. Or even, in another context, when your skin colour is not white, ‘you are below our position’.

YL: Yeah. So especially in the case of Womanifesto, it is really about female leadership. It's about women empowering other women to believe that you are not inferior, that you are fully capable or as capable, as any other individual? which I think, at the time, had to be quite radical. Were you guys the only ones? or were there other similar organizations that you were aware of?

A: Yeah, sure, I mean, let's get back to the context of today. In society in, say, Southeast Asia, maybe globally as well, the position of women is somehow like a minority, and this male domination is so obvious. So, we have to stand up and fight for our rights.

And that's what I've been doing with other minority groups, like Indigenous peoples. Because within that situation, whether it be the women or the minorities, they are basically in the same position within this context of the system today—in this global system.

YL: Do you not think that things have somewhat improved?

A: In some places maybe, in some societies or some communities it is improved, but not all. And actually I learned from my female activist friends during the pandemic, for example, when people stayed at home for about two years and when many people lost their jobs because a lot of companies go bankrupt, the violence against women is rising—and this is recently.

So, then we cannot just generalize what is happening to the struggle of the woman. Because time can also change and situations change.

YL: The question here is really: was it much more difficult, for women to gather in the early 90s, than it is now? Because, women are slightly more educated and so they're more empowered to do things, whereas it was lot harder in the 90s. So, was Womanifesto an exception or were there other similar women's centered kind of groups?

A: The difference with that time and today is that the struggle of the women is still ongoing, right? But then, with the connection through social media with this technology, one group can connect to another and they can collaborate and support each other. This is the positive side of it, but the struggle is still ongoing.

YL: Absolutely.

A: There are also more people coming from educated groups, they are also more aware and more supportive.

YL: So speaking from the perspective of a historian, on my part and also what I do with my students, what they, they are learning about this idea of lost history or forgotten histories. Especially in the 90s, at the moment something is created, if you don't document it, it's gone. For many of these events or artworks we have to rely on our memories—what you remember, what you are the eyewitness to and these kind of eyewitness accounts of what you see. However, these memories are also fading. I find that that is something we are trying to capture here, that kind of recuperation of what happened at that time, and to give back to that community, whether it's a female centred community or female history or whatever it is.

I am wondering, is there anything else that you would like to share with us about those moments that were shared across the contemporary art community? In the 90s, did you feel like you were part of something really exciting or really radical? Is there anything that you can now remember that you would want to share with us that could potentially be important, for piecing together more accurate history of women doing things in the 90s?

A: Well, from what I have experienced, of course, that kind of movement is very important because this is empowering the women, and giving them space to express themselves—especially with a group like Womanifesto. But there's something I developed further later on, the idea that, after empowering the women themselves, working together, supporting each other, that's actually in my practice.

I realized we also have to do something concrete, you know, not just creating artwork. For example, I have been working with communities in Indonesia, Tibet and also in Germany to empower the community of women by doing something real, doing organic gardening, for example, to provide the food for their family, the healthy food.

This really gives a sense of hope for the future because, lots of food production today is controlled by big corporations, and a lot of them are unhealthy. But, the so called green movement is also controlled by corporations and so the price of the so-called organic food is so high.

This means that people cannot really, enjoy it, especially of the middle to lower class, they cannot have it. So, with some friends, activists, woman activists, environmental activists, but also artists, I try to develop this new kind of idea and movement.

YL: This is much later, is it not?

A: Not during the 90s. Yeah, early 2000’s.

YL: Well, there are a lot of performances in the 90s. And because you were obviously one of the trailblazers.

A: Yeah, I did performances as well, but later on, when I realized this need to do concrete work, I develop performances with community too. So, I develop the kind of the so-called community-based art project, so we are doing performance together. There is one specific performance art work called Flag project, which I developed from 2006 and ongoing until today.

This is a very special kind of artwork, with the community. But, it's not just limited to performing or creating artworks, it is also dealing with concrete things like doing organic farming, managing the trash and recycling. And even in some, places like, Tibet, we were planting trees, reviving, nomadic culture and lifestyle, and then creating alternative energy system besides managing the source of water.

YL: Yeah. I can't help but just keep linking that that to your project Mega city. I know you don't remember very much about it, but when I scroll to some pictures that Varsha sent, she must have documented it. I haven't seen the catalog myself, do you have a copy? She said she would share it with me.

A: Maybe I have it, but now all my stuff is with my daughter.

YL: So I think, you know, it looks alike. You working with trash that's as early as the 1999?

A: Yes. That is from 1990’s to early 2000 I made that project, created that project also with not only Thai. Right. I met the artist in APT Asia Pacific trainer. So I met the group of artists there and I said ‘hey, let's do this thing, let's create this kind of project concerned about the environment.’

YL: Yeah, I just noticed that it was 1996. It says there, but then.

A: Yeah, the idea is based on that. But then I developed it further with bigger communities of Asia Pacific. Yeah, yeah.

YL: Which project is that? Which one? APT. Is it? [The IP beacon].

A: APT. I think it is, when I was invited. This is in 2003.

YL: 2003. Okay. So, there is 'Nation for sale', 'Handle with Care', that's in 2003.

A: Yeah

YL: I find that it has all these connections, and it always brings us back to 1996, these early moments when you are in Thailand, which is very interesting.

A: Yeah, that was a very good moment for me because, when I got supported in Western countries, these was also a cultural gap. Which is fine because then we can learn from each other, but when I got stranded in Thailand I discovered, oh, this is actually a very strong connection.

YL: Yes. I really have to ask this, and it would be the last question: how did you end up in Thailand in the first place? Like how did you end up in Chiang Mai and then in Bangkok?

A: Well, I was invited by the Chiang Mai Social Installation Festival. Right? Yeah. To come and join the festival.

YL: So you were in Sydney and then you went there?

A: No, I was in Perth, not in Sydney at that time, because in Sydney was my first escape from the, military regime. And, in 1994, I was in Perth to escape from Islamic hardliners—they are two different times. Anyway, so I got the invitation to go to Chiang Mai and I was so happy to meet this, community and also the group of women, of

artists. They're very, active and very, progressive, you know.

YL: Did you meet any fellow Indonesian artists there?

A: Not really at that time

YL: I'm trying to think of some and I can't seem to recall any.

A: At that time, I was probably the only Indonesian and I got support from Womanifesto and from [ ] later on. Besides other groups of artists. And then I loved the food, so then I decided ‘I'm not going back to Perth, I'm going to stay in Thailand.’

YL: And how did you support yourself during this time?

A: Well, at the time, I was working for a studio. A company where I became the, how do you call it? the one who checked the designs.

YL: Was it commercial?

A: Yeah, it was commercial. So that's how I worked for money at the time, because [Manit] was the photographer of that company. And then I'd become a kind of designer, I was checking ‘this has to be like this’, ‘this has to be like that’, ‘maybe change the color a little bit.’

YL: And how long did you do that for?

A: Since I stayed in Bangkok, I stayed in Chiang Mai for about around six months. I got an offer to teach there, but the salary was very small, then I got offered this job in Bangkok, and the salary was good. So I moved to the Bangkok.

YL: So you can survive.

A: Yeah, and also [ ] invited me from time to time to have, a class in his university, you know.

YL: Did you give talks?

A: Yes, and I got fee for doing that.

YL: And then Nitaya has a studio that also teaches children, I think.

A: Yeah, but at that time, I didn’t do that because my focus was not on children, it was more about the culture and how, you know, the, dynamic of this intercultural kind of communication because that is the Southeast Asian kind of situation. Especially in Southeast Asia, all cultures from all parts of the world have mingled for thousands of years.

This is what is so interesting for me and what is also important for people to understand, especially the so-called local traditional wisdom that is based on the principle of unity in diversity. This is actually happening in all of, Southeast Asia. And this is also what is needed today in this global world.

How can we live together peacefully and not be manipulated and abused so easily by those people who are obsessed with power and money?

YL: Okay, my last question Iani is about critical feedback

Has there been anyone at that time, during the 90s, who has been, formative to your work? Maybe Apinan or Varsha? Did you receive and critical feedback that you remember? You know, support comes in many ways, including, I suppose, critical feedback on your work.

A: Well, If I remember now, I think about this idea about culture and religion. So, of course I got some different opinions from people who have different ways of thinking. Yeah. But since I'm based in that principle of unity in diversity I don't have any problems if people have different opinions. Yeah. For example, I've been working with my colleagues from Passau University since 2012 until today, and most of my colleagues and friends there are atheists, they don't believe in religion. But it's not problem, I can work with them, especially because the focus is supporting and helping others.

So, it doesn't matter if they don't believe in God, if they don't have religion it is not a problem at all for me.

YL: I can see now why, you know, you can you get along with so many people. You have showed us how your personality your value system has made it, I don’t know about ‘easy’, but you make friends.

A: Yeah, that's the reason I can actually work with any group of people. Another example is with this, Tibetan Buddhist tradition that I learnt, which is originally from Indonesia, but a lot of Indonesians, you know, we have the largest Buddhist temple in the world. So, this tradition in, especially the, the so-called [ ] sect or the Yellow Hand led directly by the Dalai Lama, the tradition comes from Indonesia during that period of time.

It was brought to Tibet by a monk from India named [Atisa Deepankara Srijanana]. He was considered to be the pioneer of a new kind of Buddhist teaching. That principle, it is not atheistic, but it is called non-theistic, so they don't talk or busy themselves with the concept of God, they don't really discuss this concept of God—it is more about who we are as human beings, with our positive and negative potential, what is our responsibility in this life? What should we do? They never really talk about God, although they are not against it. It's just not the main kind of issue in that way of thinking.

YL: This is really great. Thank you so much Iani.

A: Thank you. Thank you.

YL: This is really wonderful. So ,I might follow up later on. We'll see. I want to, you know, some of what you, you know, whatever that we kind of mention along the way just now and clips that we could show.

A: Right. And I will send you also some images related to what I have been we are talking about or explaining.

YL: Yes, that will get of it and we'll see what we can do with the post. What do you call it? post editing.

A: Okay.

YL: Yeah. and then maybe Varsha wants to respond to some of this, I don't know. I'll send the recording to her.

A: Good. There will be nice, actually. Yes. Because then, yeah, she will, go back to the past and then.

YL: You know, I can.

A: Remind me of something that maybe I have forgotten. It is too long.

YL: Ago I, you know, and. Yeah, but, you know, it's still it's still nice. It's still nice to have a conversation about.

A: This, too. Yeah.

YL: Yeah. Thank you so much, Iani. You take care.

A: Thank you so much to take care of you. Bye bye bye.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.