By Chantawipa and Chumpon Apisuk

Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

This text was first published in Womanifesto: Flowing Connections, Nitaya Ueareeworakul et al. (eds), exhibition catalogue, Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, Bangkok, 2023, pp. 52–55.

Concrete House was founded in 1993 in the Northern suburb of Bangkok, Nonthaburi with three main missions: establishing as the head office of EMPOWER foundation; as a sex workers resource centre, community interactive centre; and an art centre specialising in performance art. EMPOWER was a sex worker community organisation. Once or twice a year the organisation would hold international and regional sex workers meetings and workshops, often parties. Concrete House held several community meetings on various issues, such as HIV/AIDS, rural development related issues, gender equality, women, ethnic, and marginal rights, etc.

In art, Concrete House was also the office of Asiatopia International Performance art since 1998. It hosted the International Performance Art Conference in 1997 and several others, such as Toxicity International Fax Art in 1995, Live Art events in 1996, including the first Womanifesto exhibition in 1997. In 2004, Concrete House was the office of Silpa, a Cultural Program of the International AIDS Conference, and an action program of the conference community section.

During 1993–1994, Bangkok art was very much a local one. There were very few international links and it was not often that Thai art circles hosted international art shows. The political front was intense as the mass demonstrations were crushed by the military in May 1992. This left 48 people killed on the streets and many people were jailed. The incident was considered the biggest bloodbath after the massacre in Thammasat University ground in October 6, 1976. However, the political nightmare was still fresh and the whole society was in the process of waking up to the new situation. The art community needed to wake up too, Concrete House, in collaboration with the student movement, organised an action art at Thammasat University ground to commemorate the student-led uprising of 14 October 1973, in order to lift up people’s spirits.

It is not right to say that there was not much going on internationally. In 1995, a big public art event like the ‘Chiangmai Social Installation’, which brought international artistic practices together, shook Chiangmai into an art city while the Bangkok edition of ‘Cities on the Move’ was organised several years after that. However, Concrete House was not the only space run by artists, in Bangkok there were Studio Xang, a community-based arts organisation; AARA About Café near Chinatown, a meeting place for artistic people with a gallery upstairs; and Project 304, a small experimental space in suburban Bangkok.

On one hand, since Thai culture was made out to be homogenic, which made all hybrid culture a taboo, the hybrid art activities were simply an ‘alternative’ type as a gesture to accept the ‘NOT THAI’ brands as subordinate to ‘THAINESS’. Although we may not see this much on the surface nowadays, when the country needs to open to the world, ‘international’ has become acceptable.

The movement like Womanifesto, on one hand, was a hybrid one. Despite the international acceptance of the events, Womanifesto was just an ‘alternative’ artistic activity, to be accepted in Thailand. It is perfect to organise Womanifesto in the rural country farmland rather than finding an art space in Bangkok to emphasise the notion of ‘outsider’, which might be the real meaning of the Thai notion of ‘alternative’.

This article focuses on a certain part of Womanifesto in relation to the events which came before and partly led to it. However, this political link was important to give an overview of the situation at the time. Thailand activists’ movements around political infrastructure, humanity issues like women’s rights, and children’s rights were swept under the rug. But once the political dust had settled, these issues would definitely be brought up again. People’s rights issues are a part of democratic development since people need time to feel stable enough to discuss them.

In 1994, a few women activists got together to open a small public discussion at Concrete House on women’s role by means of cultural terms, ‘like a woman’, using the images of Georgia O’Keee and flower painting as an image. The phrase ‘like a woman’ on one hand was a phrase to degrade a man for not acting upfront ‘like a man’, which seems to identify the role of women as ‘someone behind’. The event attracted a small audience and very little publicity—it was something new for women’s issues to be discussed in an art space. At the opening, Noi Chantawipa Apisuk, the founder of EMPOWER Foundation, was a host speaker. She posed a question: ‘Have we ever asked whether prehistoric cave painters were men or women?’, nor whether these were the roles of women and men at that time. Though we did not remember the response, it still needed an answer. However, the discussion emphasised how women see themselves, identifying whether there was such a thing as ‘the women’s role’. The discussion seemed to have less impact. After the forum ended, a few women artists came to Concrete House and started a series of meetings about organising more women’s art events.

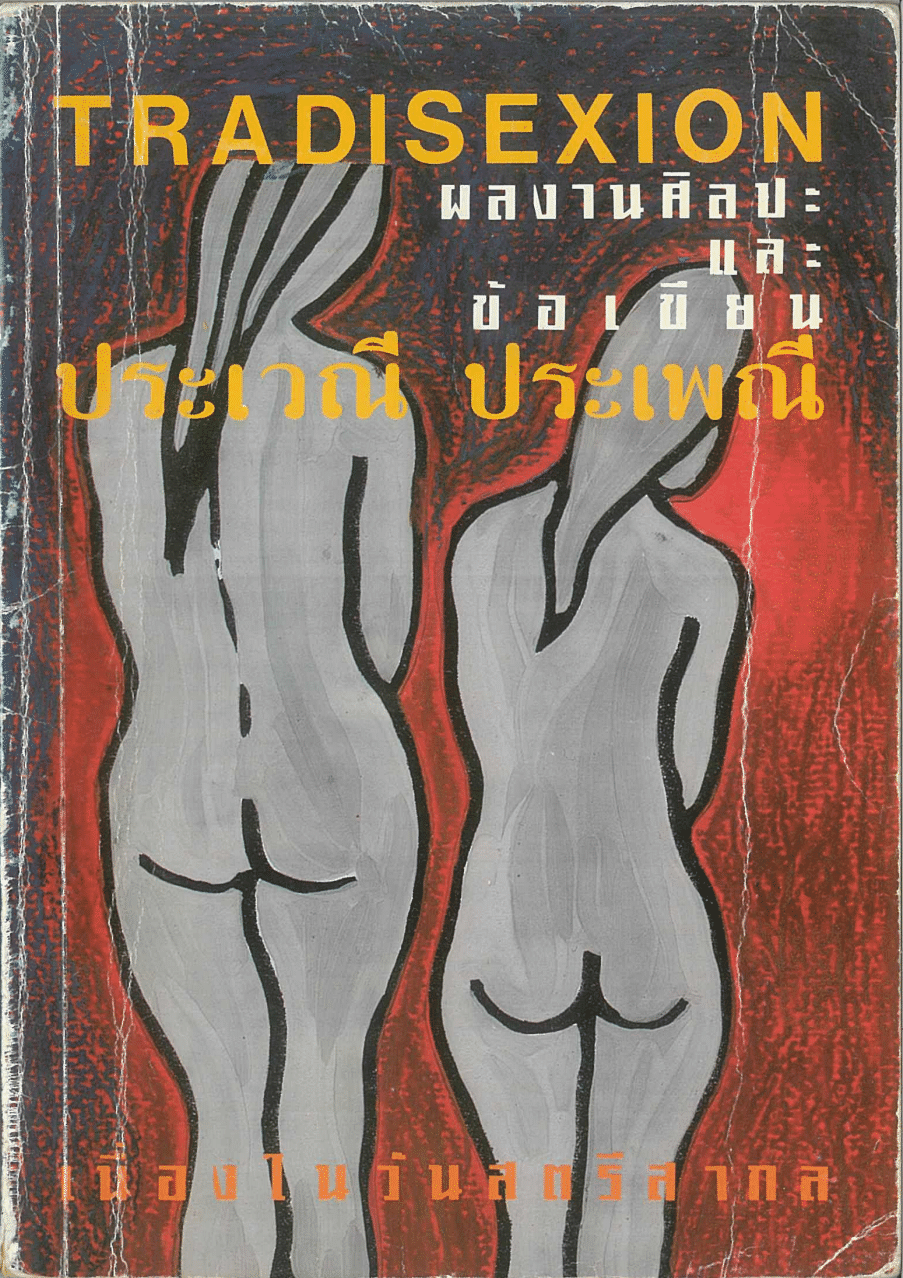

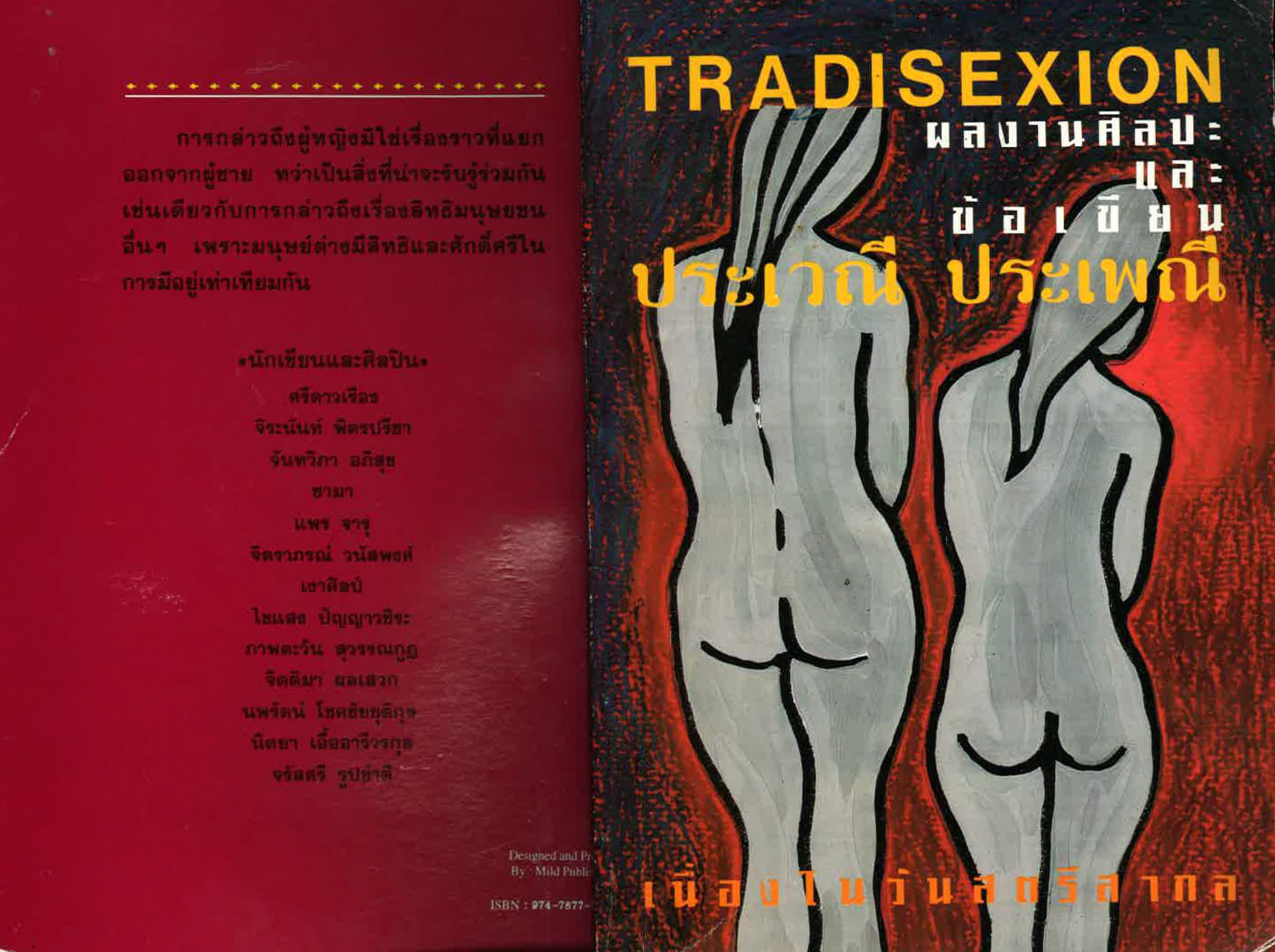

By March 8,1995, through series of meetings, a women’s art event, ‘TradiSEXion’ (‘ประเพ้ณ่ ประเวูณ’) was organised at the Concrete House. The exhibition went well and received good publicity and a bigger attendance than the previous one.

In Thai, the word ‘Pra-pe-nee’ (ประเพณั่) and ‘Pra-ve-nee’ (ประเวูณั่) are borrowed from Sanskrit and derive from the same root, Pra-pe-nee is used to explain tradition while Pra-ve-nee sexual intercourse. Does it mean that traditional practices in Thai culture are all about sexual relationships and the value of sex? This is the ingredient that coils up these two words together into another word, ‘Tradisexion’, which also shares the same sound with the word ‘dissection’. The word ‘dissection’ or ‘to dissect’ is appropriate to investigate women’s issues, and it goes the same way with the use of the word, ‘Prapenee’ and ‘Pravenee’.

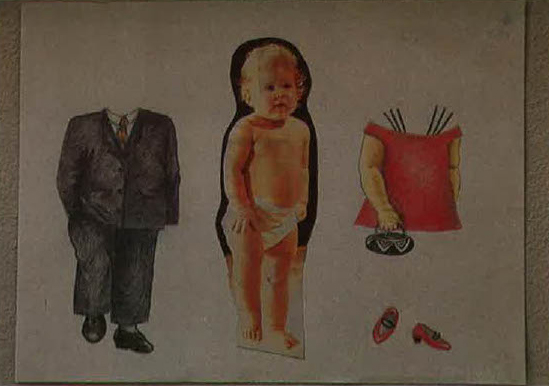

Jittima Pholsawek and Nitaya Ueareeworakul were initiators and coordinators of the exhibition. They proposed that the event would combine art and literature, women artists, and writers including Khaisaeng Panyawachira, Phaptawan Suwannakudt, Nopparat Chokchaichutikul (known as Mink Nopparat),Nitaya Ueareeworakul, Chrasri Rupkhumdee, Sri Daoruang, Chantawipa Apisuk, Chiranan Pitpreecha, Prae Jaru, Shama, Jiraporn Wanaipong, Ngaosilp, and Jittima herself... They were prominent women who were famous as the leading artists, writers, and activists. Though ‘TradiSEXion’ was probably not the first women art event in Thailand, it was the first women’s art event focusing on women’s role in society organised by women. In terms of content and context, the exhibition questioned many aspects of traditional values related to how women should behave in the society and how women should sit (while men standing) in the lower position when they were with men.

These statements were presented clearly in some powerful works. For instance, Jittima’s work, Pu Ying Haam Khun / women not allowed, was a simple snapshot of Buddha statues images with a small sign board next to the right corner of the picture written in Thai ‘ผูู้�หญิงห�ามขึ �นิ’ (women not allowed). This sign could be seen in many temples, particularly in the Northern region of Thailand, known as common among temple goers. Restrictions on women placement and misplaced position in Buddhist temples were accepted, and now were questioned publicly for the first time in an art piece. Another one was Phaptawan’s installation, A-Ko-Jorn (อโคจร)– No Passing, she hung women’s sarongs in the gallery above the head height, which was considered offensive to some male audiences especially those who wore amulets, and etc… These two artworks directly challenged ‘Tradition and sexual roles’, as if this was the only meaning of traditional value.

However, we have to give credit to the organisation leading this exhibition and giving unconditional freedom to make this event happen, EMPOWER Foundation led by Khun Noi, Chantawipa Apisuk. For Noi, sex workers in society were valued the least among all women because sex issues were attached to traditional values.1

When we talk about sexual intercourse and selling sex, it automatically highlights the devaluation of women towards sexuality. Even though there are many men doing sex work these days, men’s status always marks higher or above women.

In her writing about the story of Tip, Noi tells a true story of a sex worker who was about to marry her foreign boyfriend in Europe. She had to return home in order to verify her existence as a person by the authorities—’A village leader who she did not know or had never met, many years younger, happily signed the paper to approve that she was born and once lived in the village in which he had just become the village chief.’ At the end of the story, Noi asked if it would be the same if she was not coming from a poor, uneducated family, and met her boyfriend in a Patpong bar, where she worked.

Nopparat Chokchaichutikul stated that ‘We are not born women’, and many writings in the catalogue book describe how women grew up.2

Society today has advanced enough to accept gender over sex. More gender rights value human rights, however, women’s equality is still very much an issue. Many rights advocates are hoping that gender rights would elevate the issues of equality under the law and gain some benefits from it. The question is, have women really gained more respect than they used to?

Though ‘TradiSEXion’ sent strong messages to the public through the media, the context did not have much impact on the women’s movement but more like another art show with little notice. Art was not a major social movement then, the role of art functioned in small pockets of people in society and had never been a big thing socially.

However, this small show finally started a new platform in Asian art circles and probably in the global women artistic platforms that were made specifically for women, ‘Womanifesto I’ in 1997. This was, for the first time, women art in action was shown in public, it was an eye-opening event for many. Womanifesto was born.

One event brought up other events, so the idea could be prolonged, continued, and brought into action after action to make numbers of lives blooming. Thanks to the continuity of Womanifesto, it still has an impact today. We congratulate the founders of the festival and the platform that later become a movement. I would like to mention a few important names of this discovery: Nitaya Ueareeworakul, Phaptawan Suwannakudt, and Varsha Nair for keeping the idea up until these days.

1 Additional note from Phaptawan, whose work ‘Nariphon’ was in the subsequent rst Womanifesto exhibition in 1997, the idea was constructed following the notion of the initial argument from the exhibition ‘Tradisexion’. It re ected the true incident when a twelve-year-old girl was sold to brothel agents by her own parents in front of a temple. e work addressed the issue that girls are not allowed to ordain as monks, therefore they must pay gratitude to parents the other way. e notion of ‘Luk Sao mii waii kaii, Luk Chaay mi waii Buat’ (ลู่กูสาวูม่ไวู�ขาย ลู่กูชิ้ายม่ ไวู�บวูชิ้ / girls are for sale, boys are someone to ordain to make merit) raised the very issues of ‘ women not allowed’ (ผูู้�หญิงห�ามข้�นิ) in many places.

2 Nopparat cited Simone De Beauvoir’s statement ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a Woman’. Simone De Beauvoir, The Second Sex, H.M Parshley (ed.), H.M. Parshley (trans.), Jonathan Cape, London, 1953. p.273.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.