By Varsha Nair

Please note that this publication is currently under review and will be subject to changes.

This key note was presented on May 19, 2022 at Zurich University for the symposium, In Light of Crisis: The Fraught Significations of Contemporary Biennials.

How do I even begin to define a large chunk of my life—in this instance, a significant twenty-four years I spent in Thailand? This was a time that was personally and creatively enriching, and rhythmically punctuated by Womanifesto. Starting with my arrival to live in Bangkok in 1995, it seems our paths were destined to cross. And not only that—they are still firmly entwined in a growth of creativity that is neither planned nor pruned to fit any predetermined shape. I remember at some stage being asked what the effort I put into Womanifesto means to me as an artist. I immediately replied: it is my art practice—that invisible labour that is seldom acknowledged but is, as every artist knows, elemental to our practice. All the nuances—the collaborations, bringing people and things together, the conversations, the ups and downs, the flow of ideas, the momentum and the pauses—become part of my own growth as an artist. Such connections once formed root deeply and they continue to flourish.

When I was invited to be keynote speaker for the symposium ‘In Light of Crisis: The Fraught Significations of Contemporary Biennials', held at Zurich University in May 2022,[1] it was a role I donned for the first time. I started to unpick terminologies, and to think about how in many ways they go to fix formats and direct our thinking. As an artist this makes me uncomfortable. Yes, one needs a structure to get things done, but structures as they are played out in artistic settings tend toward having to fulfil some form of internal or external agenda, even if they often attempt to project or pretend otherwise.

I associate the word ‘keynote’ with music: a fixed note that one hears and follows to get the tune right. It leads me to think about flexibility, specifically within given notes of Indian classical. Raga, literally ‘a colouring’, requires an ability to improvise and create with a set of notes and their tonal variances; in so doing, one stirs emotions, or ‘colours the mind’. Usually, the accompanying tanpura is tuned to two notes as a point of reference, providing a background drone; there is no set composition written or handed out to sing or play—just a handful of notes to juggle with—and a musician or singer must improvise, explore and come up with new combinations each time.

And, so, each artist presenting a raga makes it their own. This freedom to create is, as I experienced as a student of classical Indian music, enticing and at the same time nerve-stirring. Just when you think you have gotten somewhere, a multitude of paths and readings and renderings open up and present themselves. You find yourself on a sensory threshold. Having reached somewhere you find yourself in-between, in a liminal space that becomes a key one from which you can reflect on what has passed, what is in the here and now, and what could be met next. In making the unseen seen, so much more remains invisible, and it is important to stay with the invisible … to step over the threshold so as to meet the unexpected.

The reason for a journey is not always to arrive at any fixed point but to open up to encounters on the journey itself, and this thinking was at the root of the picnic idea for the ‘Womanifesto Workshop 2001’, when a group of local and international women artists left Bangkok and headed for a remote farm in Northeast Thailand.

Back in 1995, which is when I moved to Thailand, Womanifesto had already been set up by a group of Thai women—artists, poets and writers, as well as activists—following an exhibition titled ‘Tradisexion’,[2] which was also held in 1995.[3] The name ‘Womanifesto’ had been coined by Nopparat Chokchaichutikul (Mink). Influenced at that time to probe further into Simone de Beauvoir’s statement, ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman’,[4] Mink started looking up dictionary definitions of all words starting with ‘man’ and arrived at ‘manifesto’. To this she added ‘Wo’ in front and it thus became Womanifesto—an exhibition, bringing together a group of local and international artists, that took shape in discussion with some of the participants of ‘Tradisexion’. Establishing a platform to support voices from different parts of the world to come together and be heard allowed the group to take control of the narrative by foregrounding women artists and start to make visible their points of view.

1995 was also the year that the Fourth World Conference on Women took place in Beijing, and the artists were aware of its global agenda of pushing for gender equality. Facing a lack of spaces where they could meet and show, Womanifesto in its first event, in 1997, was set to present an exhibition of works by a group of eighteen local and international women artists.

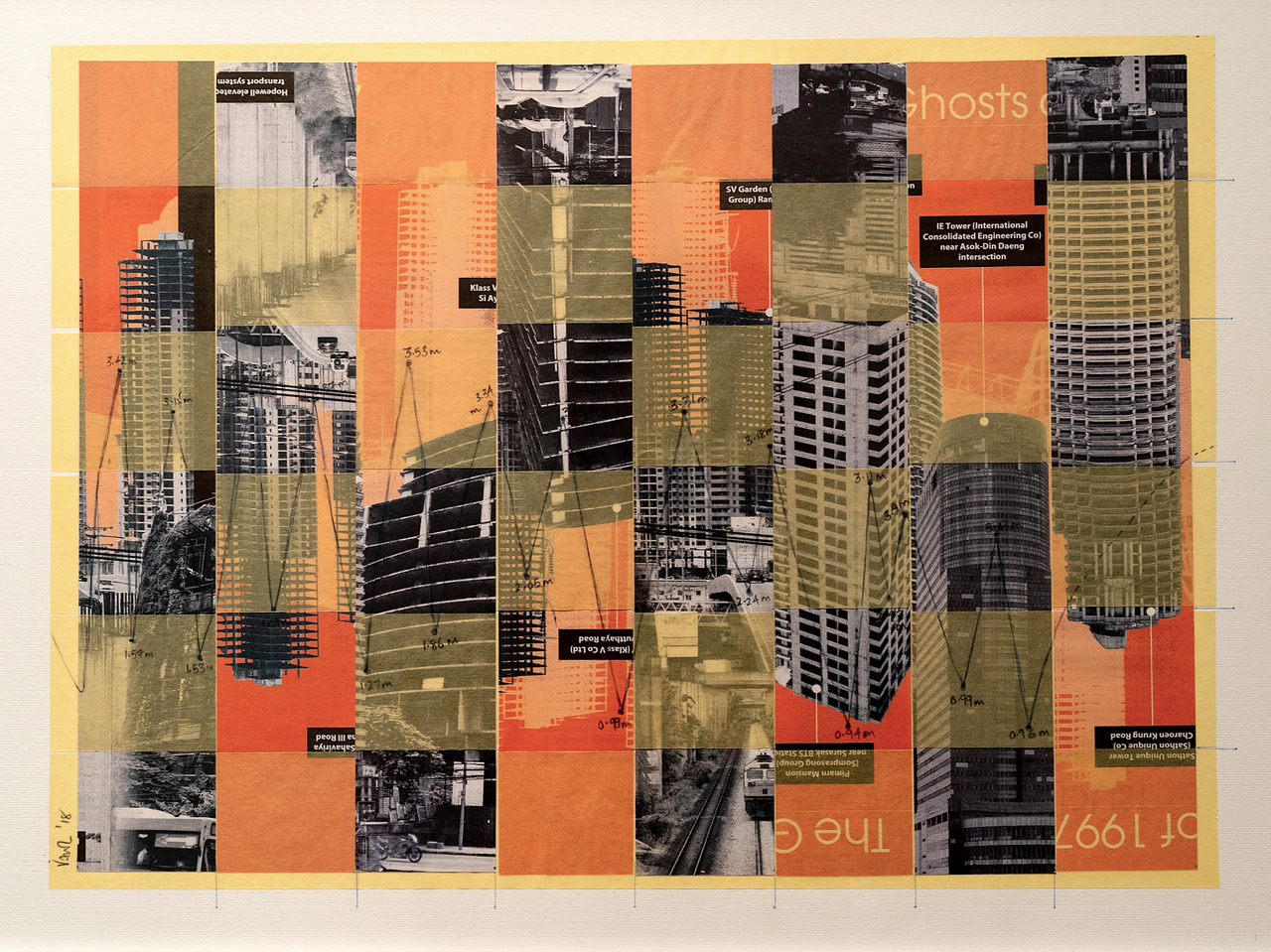

When I was invited to participate, what excited me and struck me as significant was the opportunity to become part of a rare gathering and the chance to meet other artists, some local and some coming from neighbouring countries as well as further away. I was the last to be added to the mix, and was soon invited by Nitaya Ueareeworakul to join her in organising the exhibition. It was also significant that Womanifesto was led by artists from the start—it has remained so to date—and that it followed an open organisational format whereby any artist who had an idea and was willing or able to give time could form or join the organising team. The first Womanifesto exhibition opened to mark International Women’s Day on 8 March, 1997, amid the looming Asian financial crisis that unfolded soon after. The repercussions of that crisis reached well into the future: some of the so-called ‘ghost’ buildings, skeletons of constructions that were stopped as finances ran out, in Bangkok still remain unfinished today. I started collecting newspapers and inserts—stock market pages and follow-up reports about the crash—as well as images of Bangkok’s ghost buildings, to make what I called woven landscapes. Much later, I returned to these images and this archive to install a video projection on one of the ghost buildings from the adjoining Bridge Artspace in 2018, before I left Bangkok for good. The economic and political upheavals were always in the background and felt constant. Following coup after coup ousting elected leaders, the military and monarchy is now firmly in control. The current reality in Thailand is one of ongoing political turmoil, clampdowns on freedom, arrests of students, and disappearances and killings of activists. In this challenging environment, many artists, designers and students have turned to social media, which offers a relatively safe space to air the growing dissonance, connect with many and come up with strategies to speak up, meet and protest, and talk about the troublesome situation in the country.

In the 1990s, with little support for artists—especially those working independently—and few institutions we could approach for funding, it was clear that we had to stand on our own to realise our projects and exhibitions. The little funding we had barely covered our basic costs, which meant we had to dig into our own pockets, and artists joining the Womanifesto exhibition in 1997 (and subsequent events) often had to pay for their own travel, self-organise, help each other to install, and so on. We welcomed the artists into our homes, and these became crucial spaces that were conducive to informal conversations where thoughts and ideas—our realities—could be shared and deeper connections forged. This getting to know each other, communing with other artists, is not always a given at group exhibitions, in my experience, where often little effort is made by organisers to introduce participants, or bring them together to promote a sense of community and facilitate the forming of connections.

Our exchanges over meals—not in galleries—became important germinating points. We started to form strategies in informal discussions, and also through reciprocity with some of us later being invited back for events set up by other artists, such as Tari Ito in Japan, Amanda Heng in Singapore, and Sanja Ivekovic in Croatia. This was the start of a self-expanding network with a web of connections beginning to grow organically, and we were not waiting to be curated or asked.

In addition, writing, talking, disseminating, drawing focus to what we were doing—challenging the erasure we felt we were facing in being kept out of the art discourse taking place in our environment—served to firmly claim space and refuse to be made invisible. For example, Womanifesto’s practice of decentralisation, which started with the 2001 workshop and launched ongoing conversations with farming/rural communities, would not even be mentioned or be up for discussion or consideration at local and international talks and symposia. Womanifesto was overlooked in scholarly research and writings that would focus on other rural community/land-based practices in Thailand, such as Jim Thompson’s Art on the Farm, The Land Foundation outside Chiang Mai, or other such projects happening elsewhere.

The first two editions of Womanifesto were exhibitions held in Bangkok—at Concrete House and Baan Chao Phraya Gallery in 1997, and in the outdoor spaces of Saranrom Park in 1999. Apart from exhibiting, the outcome was a realisation that what we enjoyed most was being together, not just in producing and showing works but in the sharing of our stories, our thinking and doing processes, and our invisible labour, so to speak—generally the time spent out of the gallery. This led to the vision of continuing with a more open-ended creative exchange format, one with hospitality and care at its core and with no specific exhibition outcomes, except in the form of open days, which varied according to the project situation. The editions that followed took diverse forms. Rather than envisioning what the next few projects could be, what emerged and what we experienced at each one became a stepping stone to plan the next one.

After the 1999 Bangkok exhibition in Saranrom Park, which featured thirty participants and involved with complex organisation, planning and logistics including dealing with the Bangkok Metropolitan Authority (the funders), we were exhausted and decided to change course: to leave the city and head to a remote area with a smaller group. The idea was for the time spent together to be a ‘talk fest’, and to see what could emerge out of that. In 2001 we set up a ten-day workshop on Boon Bandarn Farm on the invitation of Khun Pan Parahom, one of the farm’s resident owners, with a central sala becoming a space to host local artisans, musicians, students, and anyone from the surrounding community, and where all could meet and interact. The focus was not on visiting artists making their own work, but instead engaging in a combination of various forms of exchange of knowledge and practice, as well as concentrating on art-creating processes to reach all people.

Where to Next?

Nitaya and I had been the core co-organisers from the beginning, and when she was pregnant with her first child, we discussed putting out an open call for a mail/email project that mainly I would handle. With the welcome assistance of Preenun Nana, our co-organising resulted in the publication Procreation/Postcreation in 2003. Taking a cue from mail art projects and networks of yore, the call for participation in Procreation/Postcreation was shared widely via artists’ email lists, and responses from people started pouring in from around the globe, from Mongolia to St Vincent and the Grenadines.

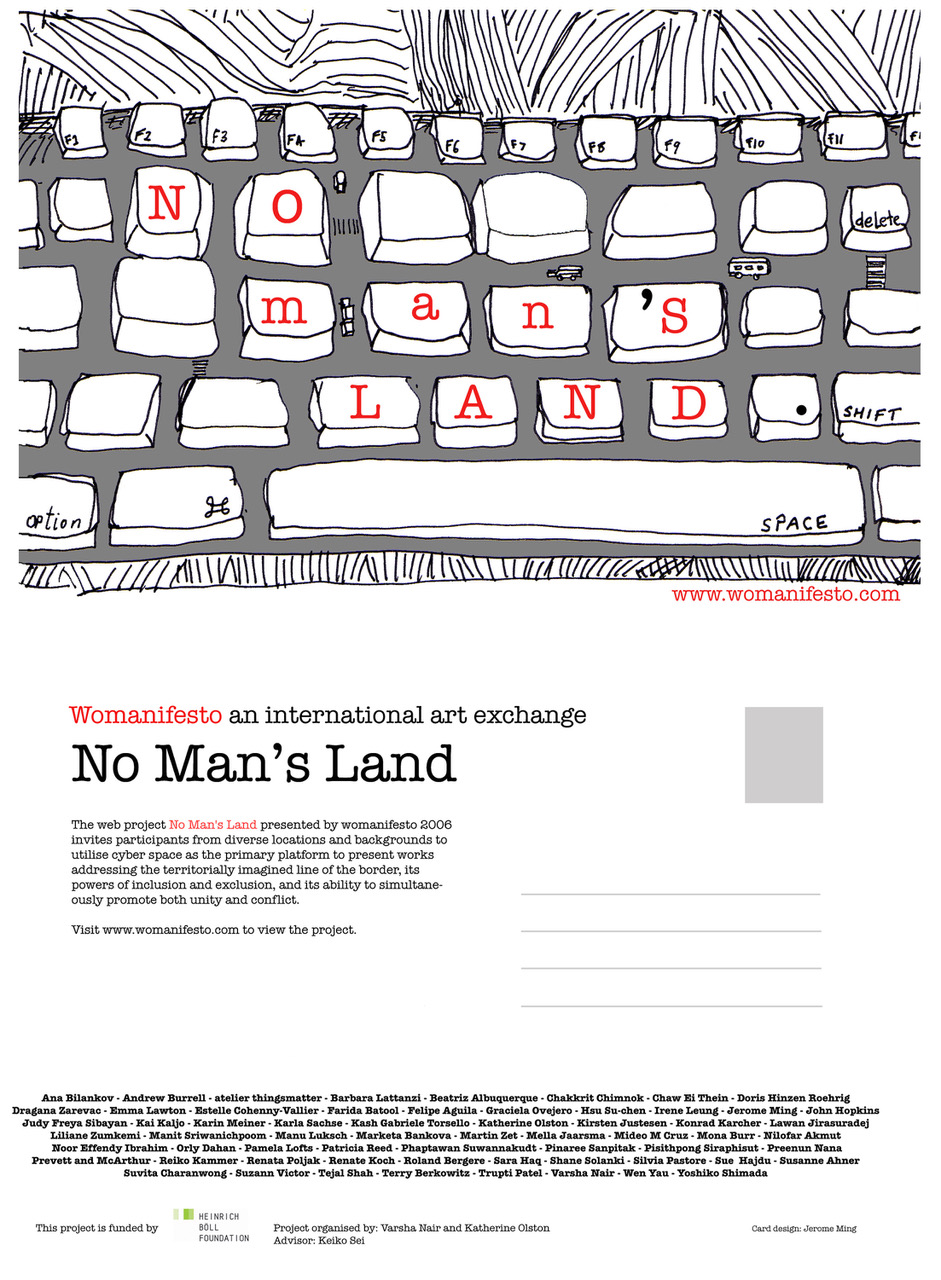

In the same year we were offered funding to establish the Womanifesto website and as a natural step we started to plan the web-based project, ‘No Man’s Land’, for 2005–06. For this project, which was organised by Katherine Olston and myself with Keiko Sei as advisor, we invited sixty-five participants from diverse locations and backgrounds to utilise cyberspace as the primary platform to present works that addressed the territorially imagined line of the border, its powers of inclusion and exclusion, and its ability to simultaneously promote both.

Wanting to reconnect with the farming community and continue the conversations begun in 2001, in 2008 we established a residency project on the same farm, Boon Bandarn Farm in Si Saket province, north-east Thailand, explicitly to explore the links between traditional and contemporary art practices. Organised by Nitaya, Phaptawan (who was also one of the participants) and myself, the residency invited Khun Pan Parahom as a participating artist; joining her were four artists linking three generations together as residents for one month. Along with developing works individually and collaboratively, students from local schools, technical institutes and the Mahasarakham art school were invited for workshops set up by the artists. While the original aim of Womanifesto was to strengthen links between women artists in the region and bolster our visibility, over time that aim developed to also include workshops with school and university students with a focus on exploration and valuing of local cultures, including artisanship. Womanifesto is one of the rare artist-organised projects of its kind to have emerged and developed from Southeast Asia, one that brought an international group of artists together and has consistently realised diverse projects to date. We sustained ourselves and continued to collaborate by remaining agile and acknowledging the other demands on our lives as artists and as women. Alongside our own artistic work, we were busy also attending to our homes and caring for our families, both immediate and extended. With Nitaya in sole charge of bringing up her children and both of us caring for aging parents, after the residency in 2008, we made the decision to take a pause and reactivate as and when circumstances allowed.

Staying the Course

I think of what has come next as phase two of Womanifesto. Almost a decade after our pause, in 2017 we started working on the archive, exhibiting it, and realising new projects.

Focusing on women’s exhibitions, archives and canon-making, Yvonne Low, Clare Veal and Roger Nelson invited Womanifesto to present at the symposium ‘Art, Digitality and Canon-making?’ as part of the ‘Gender in Southeast Asian Art Histories’ project. Supported by the Power Institute, together with the School of Letters, Arts and Media in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Sydney, the symposium included an exhibition of Womanifesto archival materials and original works at CommDe, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, and Cross Art Projects in Sydney. We also presented at the symposia in both cities. The exhibitions made publicly available for the first time many of the photographs, videos, artworks, documents, publications and other ephemera archived by Womanifesto artists over three decades. Around the same time we were approached by John Tain, head of research at Asia Art Archive Hong Kong (AAA), to digitise the Womanifesto archive, and the added exposure at symposia and exhibitions in Bangkok and Sydney became the impetus to start working on digitising the material which is now included in Asia Art Archive’s research collection.[5]

During this time, we also started planning our next project, which was originally intended for 2020, but with the pandemic’s global impact we had to rethink and adapt our original idea of a physical gathering in one place.

Facing the situation of not knowing how our realities would unfold, we decided to invite participants from previous projects to host gatherings in their respective locations instead of gathering in one place. We asked them to connect with artists living in their immediate vicinity and set up a meeting point—a tangible space to convene face-to-face whilst following safety guidelines. Thus, amidst the lockdowns, ‘Womanifesto 2020: Gatherings’ opened up conversations with various groups joining in from Udon Thani (Thailand), Baroda (India), Berlin (Germany), Sydney (Australia), Basel (Switzerland), and London (UK). The lead person in each location invited friends and colleagues and followed their own theme in relation to their immediate situation and consideration of what a gathering could be in the uncertain context of those times. What happened locally was linked in an international network via a blog set up to share experiences.[6] The questions we collectively asked ourselves were: How do we define ‘togetherness’? And how can we create and sustain support, proximity and a sense of touch across cultures and geographical borders in our supposedly post-pandemic world? And are we post-pandemic?

LASUEMO

With this in mind, in May 2021, LASUEMO—an online meeting space for gathering virtually on the LAst SUnday Every MOnth—was set up by Lena Eriksson, *durbahn and myself as an informal community based on friendship and sharing. Bridging distance to connect, especially with many still in enforced isolation even after the lifting of lockdowns (during which digitally connecting via platforms like Zoom, Jitsi and so on came to mean so much), we thought it crucial to keep the conversation going. Having opened up a ‘digital courtyard’ on the blog, we gather to find ways to be with each other and to create a pool of interesting topics with everyone’s input. It’s about communication between artists, about our situation, and about doing things together. Initially drawing from the group of artists who had been part of or connected with Womanifesto, we soon began to invite in new people who didn’t previously have any direct connection with the collective, to form an ever-expanding circle. We start each session talking about the weather in our respective locations,[7] and we then welcome presentations to input ideas, introduce collaborations, talk about new works being developed, and occasionally set up an activity that we work on together online.

One LASUEMO gathering that took place on May 1, 2022 (as the last Sunday in April was not possible, and we keep it fluid) was around mending, repairing and patching. In current times when the very fabric of life feels fragile, much mending is required to reweave relationships between people and with our environment as a whole. This led to us setting up the WeMend space—a dedicated, hands-on patch and mend community space in the exhibition ‘Womanifesto: Flowing Connections’ at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC), to invite and encourage students and the visiting public to get involved in ongoing sewing, upcycling and stitching-together activities, and in thematic workshops. Preenun Nana, one of the organising team members for the BACC exhibition, intuitively came up with the title WeMend—a play on the word ‘women’—inspired by our LASUEMO mending session and connecting it with her personal reflection on the linkages that Womanifesto facilitates.

Instead of organising a project biannually, as we had done in our early years, we now find ourselves engaged in diverse activities, even scheduled at short notice, that are flexible and organic and reflect the open-ended ethos and flow of Womanifesto.

Talking about the biennale craze, one reaction to this (which was also a comment on the political turmoil in Thailand, including the uncertainty following the 2006 military coup) initiated by the Bangkok University lecturer and curator, Ark Fongsmut, was ‘Bangkok Biennial 01’—a kind of spoof. Ark’s organisational support had been key in helping us to realise the first Womanifesto exhibition in 1997. For ‘Bangkok Biennial 01’, he asked any artist so willing to include the event in their CV, and he also printed t-shirts with the logo of the biennale on one side and ‘You missed it’, which happened to be the theme, on the reverse. As it happened, in 2018 Thailand saw the inauguration of not one but three biennales: Bangkok Art Biennale, Bangkok Biennial (an independent, guerilla-style event that launched itself as ‘the first biennial/biennale event to take place in Thailand’), and the First Thailand Biennale, ‘Edge of the Wonderland’, which was organised by the Thai government’s Office of Contemporary Art. There were many ‘firsts’ being claimed here, perhaps in an effort to play catch-up in a race to claim a place in history. I remembered reading back in 1998 about the first Berlin biennale, and it stayed with me—perhaps because at that time I had not yet visited any biennale in person, and perhaps because I had just been to a jazz festival.

In Martin Gayford’s review in The Spectator of Berlin, ‘Berlin’, as that biennale was titled, he wrote:

It must be said that the contents of the Biennale are not vastly different from those of the many other, constantly proliferating biennales (once every town that wished to raise its profile had a garden festival, then it was a jazz festival, now it is a biennale).[8]

Flowing Connections

To call Womanifesto a biennale had not entered our minds. It struck me when, in an interview by AAA in 2009, I was asked what I thought about the proliferation of biennales, and whether Thailand would be hosting one. I replied:

There has been a biennale in Thailand since 1997—‘Womanifesto’. I don’t think that has even registered in people’s minds. And the fact that it was established locally to engage globally, independently as an initiative led by artists working on a huge dose of passion and with the most basic and, at times, downright frugal funding, was way before this current ‘biennale craze’ took hold. [9]

Despite the challenges we faced personally and in terms of resources, a friend recently remarked, seeing the direction Womanifesto has taken over the years, ‘Womanifesto continues to reach a wide audience and remains part of the current discourse of community and artistic manifestation.’[10] The different editions of Womanifesto started nearly three decades ago, well before the biennale eruption in Thailand and the region, and have since stretched beyond the region to produce intergenerational and cross-disciplinary workshops as well as communal spaces for exchange, and to carve out a space for all in the still predominantly patriarchal landscape.

[1] See ‘In Light of Crisis: The Fraught Significations of Contemporary Biennials’, University of Zurich, https://www.khist.uzh.ch/de/chairs/moderne/events/Symposium-In-Light-of-Crisis.-The-Fraught-Significations-of-Contemporary-Biannials.html, accessed 9 October 2025.

[2] For further reading on setting up ‘Tradisexion’, see Chantawipa Apisuk and Chumpon Apisuk, ‘TradiSEXion: the Pre-Womanifesto’, in Womanifesto: Flowing Connections, 2023, pp.52–55. A version of this text is also published here.

[3] For the ‘Tradisexion’ catalogue see Asia Art Archive (AAA), Womanifesto Archive, Publications, Catalogues, ‘Tradisexion: The Work of Art, Sexuality and Tradition, Tradisexion ผลงานศิลปะและข้อเขียน ประเวณี ประเพณี’, https://aaa.org.hk/archive/271865, accessed 9 October 2025. For a translation of excerpts from the ‘Tradisexion’ catalogue, see Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019. For a reflection on this history, see Phaptawan Suwannakudt, ‘Before Womanifesto, In My Recollection’, Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019, pp. 175–80.

[4] Simone De Beauvoir, The Second Sex, H.M Parshley (ed.), H.M. Parshley (trans.), Jonathan Cape, London, 1953. p.273.

[5] See Asia Art Archive (AAA), Womanifesto Archive, https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/womanifesto-archive, accessed 9 October 2025.

[6] See ‘Gatherings’, Womanifesto, http://blog.womanifesto.com/about/, accessed 9 October 2025.

[7] let’s talk about the weather—the weather as a collective condition is a recent project by Lena Eriksson, *durbahn and Varsha Nair with LASUEMO participants for the forthcoming online Ctrl+P Biennale, initiated by Judy Freya Sibayan. See let’s talk about the weather—the weather as a collective condition, https://weather-here.cloud/, accessed 9 October 2025.

[8] Martin Gayford, ‘Berlin: A City Under Wraps’ The Spectator, 10 October 1998, p.49. Also available at The Spectator Archive, http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/10th-october-1998/49/fine-arts-special, viewed 9 October 2025.

[9] Asia Art Archive, ‘Interview with Varsha Nair’, Like a Fever, https://aaa.org.hk/en/ideas-journal/ideas-journal/interview-with-varsha-nair/type/conversations, viewed 9 October 2025.

[10] Email exchange with artist Jerome Ming

Varsha Nair is an interdisciplinary artist based in Baroda, India, where she studied painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University. Her works and projects have been exhibited internationally, including at Tate Modern, London, Art in General, New York, Cities on the Move 6, Bangkok, WTF Gallery, Bangkok, Lodypop, Basel, and most recently at documenta 15, Kassel.

Nair lived in Thailand from 1995 to 2019 where, as one of the key co-organizers of Womanifesto, she was instrumental in conceptualising projects that stretch beyond the traditional model of biennial exhibition making to produce intergenerational and cross-disciplinary workshops, collaborations, and networks.

Related pages

Share a Reflection

log in to share a reflection.